Behind the Scenes Couzin et al. 2011

#academia

Written by Matt Sosna on July 16, 2015

The story behind Couzin et al. 2011: “Uninformed individuals promote democratic consensus in animal groups”

Couzin ID, Ioannou CC, Demirel G, Gross T, Torney CJ, Hartnett A, Conradt L, Levin SA, Leonard NE. 2011. Uninformed individuals promote democratic consensus in animal groups. Science. 334: 1578-1580.

Background

Conflicts of interest within groups are ubiquitous in the animal kingdom. Thirst will pull some gazelles to the watering hole instead of the grass patch, recent experience with predators will give some fish less incentive to enter open water, and differing knowledge about the geography of a region means migrating birds may disagree on where to roost. The benefits of group living, such as safety in numbers and enhanced environmental sensing, are often too high to afford individuals to split into subgroups: they have to stay together. Groups therefore often have to make consensus decisions, where the outcome affects everyone. How does this happen?

For years, scientists have focused on how the interactions between the group members who want to go to destination A versus destination B determine what the group decides. The role of members who don’t have a preference, however, remained overlooked.

“People tend to think of uninformed individuals as contributing nothing but noise to decision-making, whether in neural systems or animal systems,” said Iain Couzin, Director of the Max Planck Institute for Animal Behavior in Konstanz, Germany. In the years leading up to 2011, Couzin felt that such group members had a much larger role to play in decision-making than just noise, however.

Information heterogeneity

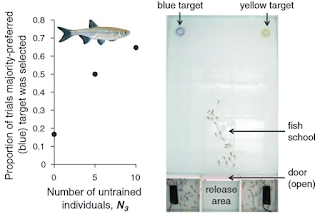

Couzin and colleagues had touched upon the influence of leaders and naïve individuals in group movement in 2005 (“Effective leadership and decision-making in animal groups on the move,” Nature) before moving on to explore other questions, but the role of information heterogeneity among group members continued to intrigue him. In 2010, Couzin had been working on modeling the evolution of collective decision-making while Dr. Christos Ioannou, then a postdoc with Couzin and now at the University of Bristol, was examining how golden shiner schools decide which destination to swim to when group members are conflicted. The shiners had been trained to swim towards either a blue target or a yellow target, but to Ioannou’s surprise, he discovered a massive learning bias in the fish: they learned much more quickly and reliably to swim towards the yellow targets. Couzin and Ioannou weren’t sure whether to throw the data out or try to address the bias in the statistics. Similarly, the outputs of Couzin’s models were proving difficult to understand.

“There were lots of ups and downs – lots of light bulbs that turned out not to be light bulbs,” said Andrew Hartnett, who worked with Couzin on the models as a graduate student. “This type of work, theoretical collective behavior, requires a healthy dose of skepticism about your own work. Are our results real or just a trivial mistake, the result of our modeling choices?”

This skepticism motivated the creation of several models, each approaching the question of uninformed individuals’ importance from different angles, to ensure their results stood. “We threw the kitchen sink at the problem,” said Hartnett. “Iain and I talked about it constantly. He is great at listening and synthesizing ideas. It was a really fun way to do research.”

“We really wanted to make sure the models were coming to the same conclusions,” Couzin said. “We wanted relatively simple models that were revealing common principles and elucidating the mechanism for what we were seeing.”

The value of bias

A turning point in the study came to Couzin while walking for the bus. “I realized the learning bias in Ioannou’s experiment was a blessing.” This bias, he said, could allow them to unite Couzin’s models with Ioannou’s experiment. Because the shiners were exhibiting a learning bias towards yellow over blue, Couzin saw the opportunity to create groups of individuals with both mixed preferences and varied strengths of preferences.

“There was quite a delay actually in running the experiments to realizing that the model really predicted the naïve effect only when there is a bias,” Ioannou said. “This realization happened over time - Iain initially suspected it and shared this with me, and slowly, with more simulations and analysis, it became more certain.”

Once all three models and the experimental work began agreeing with one another, the authors realized they had discovered something monumental. Hartnett said, “Each model serves two purposes. The first is that different levels of abstraction reveal different pieces of the answer to: why is this happening? The second is that a common result across models with very different assumptions provides increasing evidence of the fact that this is a real phenomenon and not an artifact.” The experimental work provided a test of the models, showing they really do reflect the real world.

This crucial role for unopinionated individuals is important because it explains why we don’t have an arms race for more and more opinionated groups in animal groups, including human societies. There is only so much one can gain by shouting a message; the group’s decisions will always be buffered by the members who are not heavily invested in one outcome or the other. “The tiny fraction that doesn’t care about the outcome of the group’s decision ends up determining the outcome,” Couzin said.

It’s also important to note that these results refer to the role of unbiased individuals, not unintelligent. The article, once published, generated much media attention claiming Couzin and colleagues were implying that unintelligent people are crucial for democracy. Couzin stresses an alternate point. “Much of the media claimed we were saying that less information is a good thing. As we report in the paper, having more information is a good thing. But animals are limited in their ability to get info, so groups tend to be heterogeneous.” This heterogeneity, as shown in Couzin et al. 2011, has a paramount effect on how groups reach decisions.

The article can be found here.