A business lens on precision and recall

#machine-learning #statisticsWritten by Matt Sosna on December 20, 2023

Disclaimer: the examples in this post are for illustrative purposes and are not commentary on any specific content policy at any specific company. All views expressed in this article are mine and do not reflect my employer.

Why is there any spam on social media? No one aside from the spammers themselves enjoys clickbait scams or phishing attempts. We have decades of training data to feed machine learning classifiers. So why does spam on every major tech platform feel inevitable? After all these years, why do bot farms still exist?

The answer, in short, is that it is really hard to fight spam at scale, and exponentially harder to do so without harming genuine users and advertisers. In this post, we’ll use precision and recall as a framework for understanding the spam problem. We’ll see that eradicating 100% of spam is impractical, and that there is some “equilibrium” spam prevalence based on finance, regulations, and user sentiment.

Our app

Imagine we’re launching a competitor to TikTok and Instagram. (Forget that they have 1.1 billion and 2 billion monthly active users, respectively; we’re feeling ambitious!) Our key differentiator in this tight market is that we guarantee users will have only the highest quality of videos: absolutely no “get rich quick” schemes, blatant reposts of existing content, URLs that infect your computer with malware, etc.

Attempt 1: Human Review

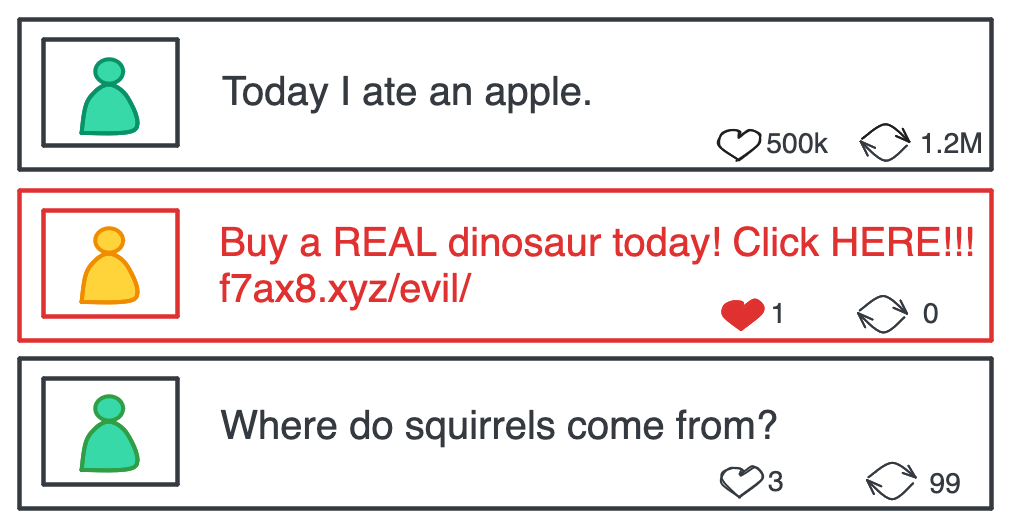

To achieve this quality guarantee, we’ve hired a staggering 1,000 reviewers to audit every upload before it’s allowed on the platform. Some things just need a human touch, we argue: video spam is too complex and context-dependent to rely on automated logic. A video that urges users to click on a URL could be a malicious phishing attempt or a benign fundraiser for Alzheimer’s research, for example – the stakes are too high to automate a decision like that.

The app launches. To our delight, our “integrity first” message resonates with users and they join in droves. We quickly reach millions of users uploading 50,000 hours of video per day.

In other words, each reviewer now has 50 hours of video to review per day. They try watching at 6x speed to get through all the videos, but they make mistakes: users start complaining both that their benign videos are being blocked and that spam is making it onto the platform. We quickly hire more reviewers, but as our app grows and the firehose of uploads only gets bigger, we realize we’ll bankrupt the company long before we can hire enough eyes.[1] We need a different strategy.

Attempt 2: Machine Learning

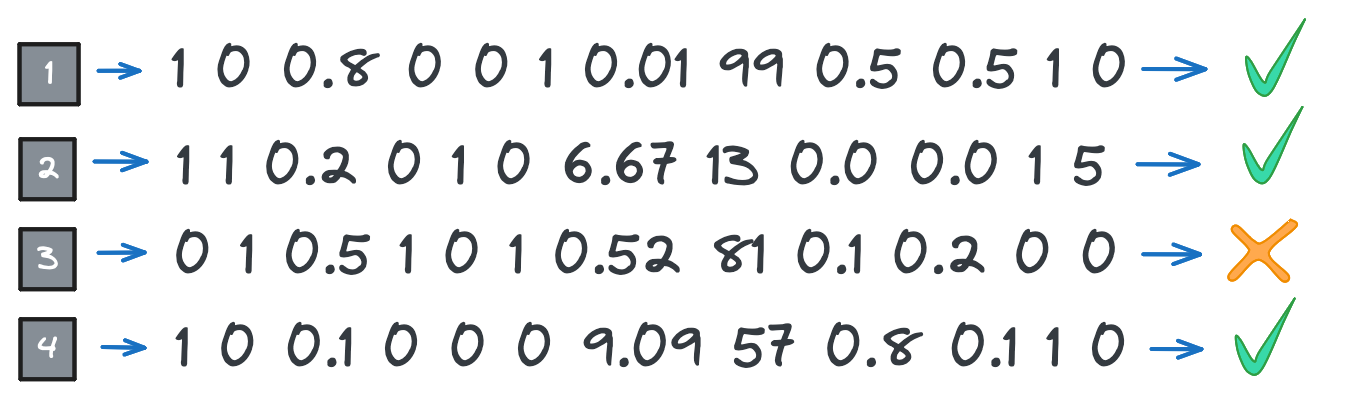

We can’t replace a human’s intuition, but maybe we can get close with machine learning. Given the tremendous advances in computer vision and natural language processing over the past decade, we can extract features from the videos: the pixel similarity to existing videos, keywords from the audio, whether the video appears to have been generated with AI, etc. We can then see how these features relate to whether a video is spam.

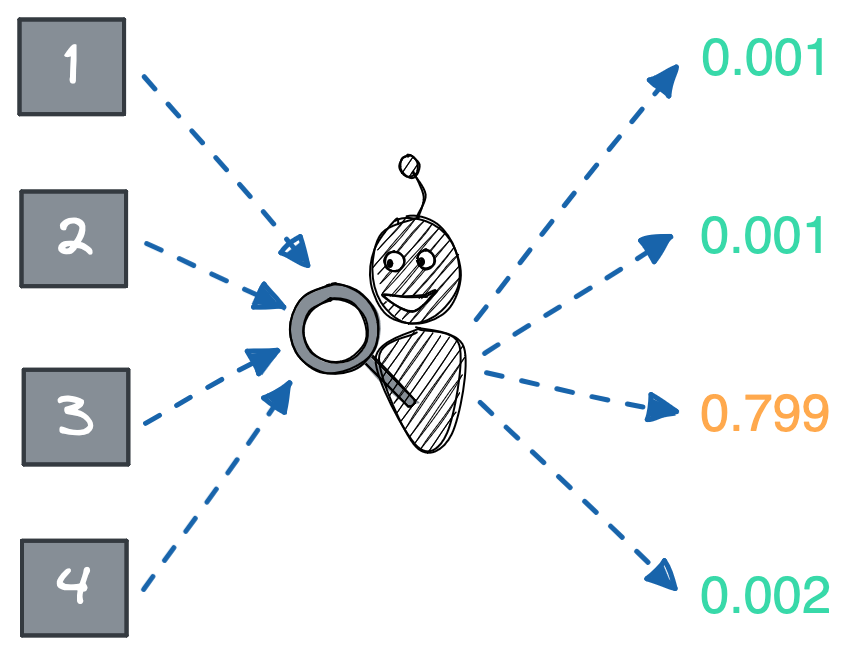

Determining the relationship between features and spam labels is best left to an algorithm.[2] The feature space is simply too large for a human to understand: features interact non-linearly, have complex dependencies, are useful in some contexts but useless in others, and so on. So we use machine learning to train a classifier that predicts whether a video is spam. Our model takes in a video and outputs the probability that the video is spam.[3]

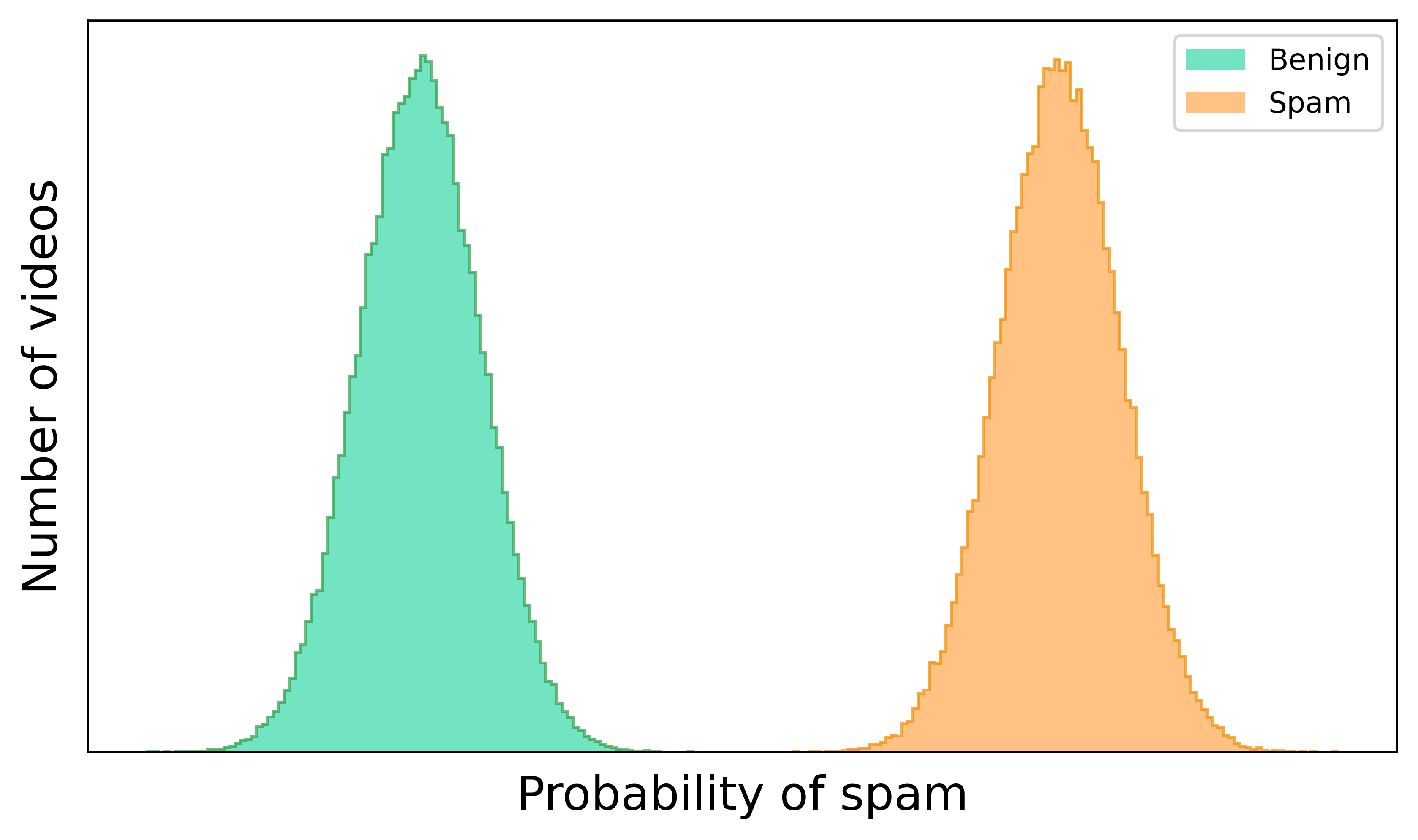

When we first run our classifier on videos we know are spam and benign, we hope to see something like below: two distributions neatly separable by their probability of being spam. In this ideal state, there is a spam probability threshold below which all videos are benign and above which all videos are spam, and we can use that threshold to perfectly categorize new videos.

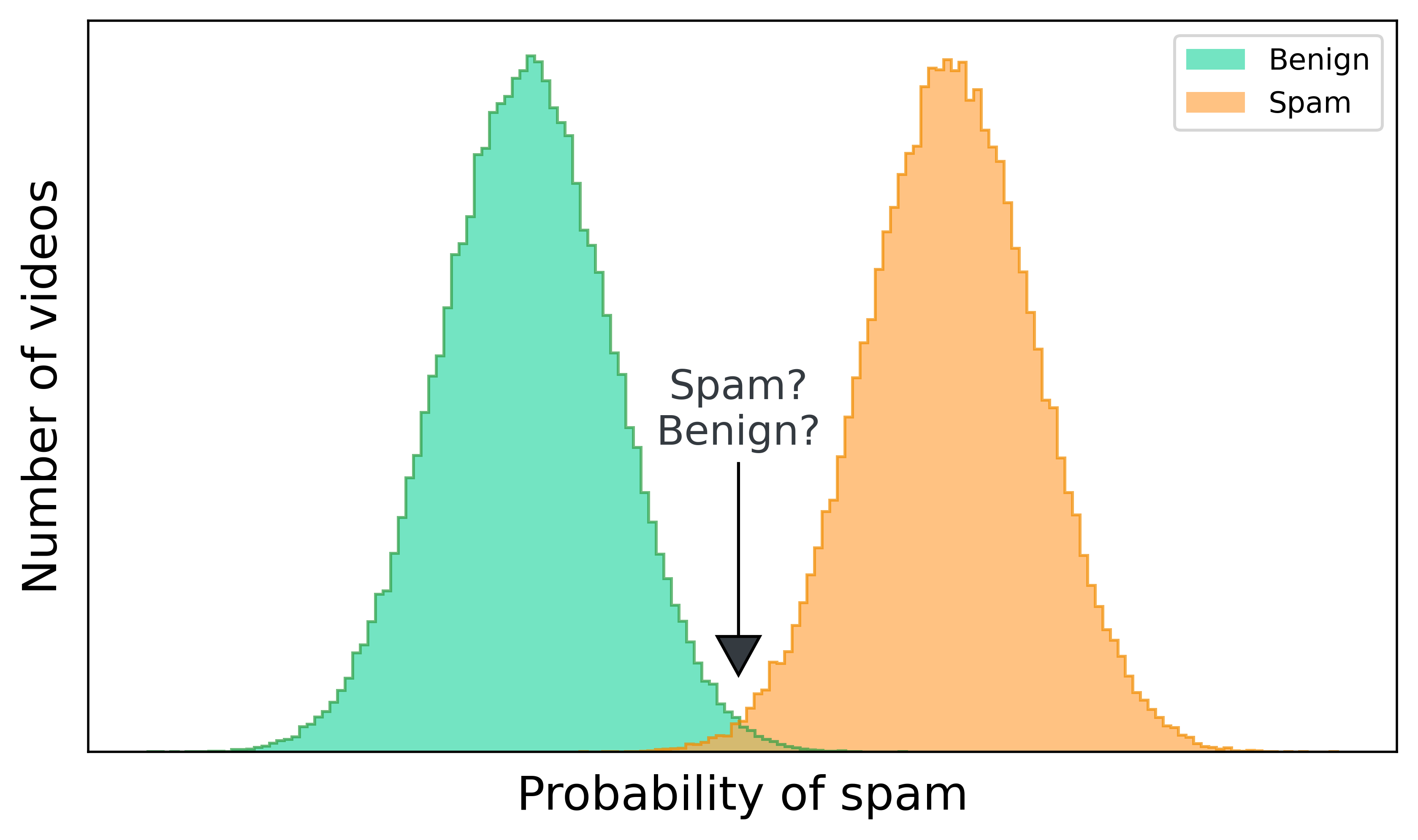

But what we actually see is that the probability distributions overlap. Yes, the vast majority of benign videos have a low probability and the vast majority of spam videos have a high probability. But there’s an uncomfortable “intermediate” spam probability where it’s impossible to tell if a video is spam or benign.

If we zoom in on where the distributions overlap, it looks something like this. Nowhere can we draw a line that perfectly separates benign videos from spam. If we set the threshold too high, then spam makes it onto the platform. If we set the threshold too low, then benign videos are incorrectly blocked.

So how do we choose a “least-bad” threshold? To answer this question, we need to understand precision and recall, two metrics that provide a framework for navigating the tradeoffs of any classification system. We’ll then revisit our app with our new understanding and see if there’s a way to optimally classify spam.

Evaluation Framework

Model Creation

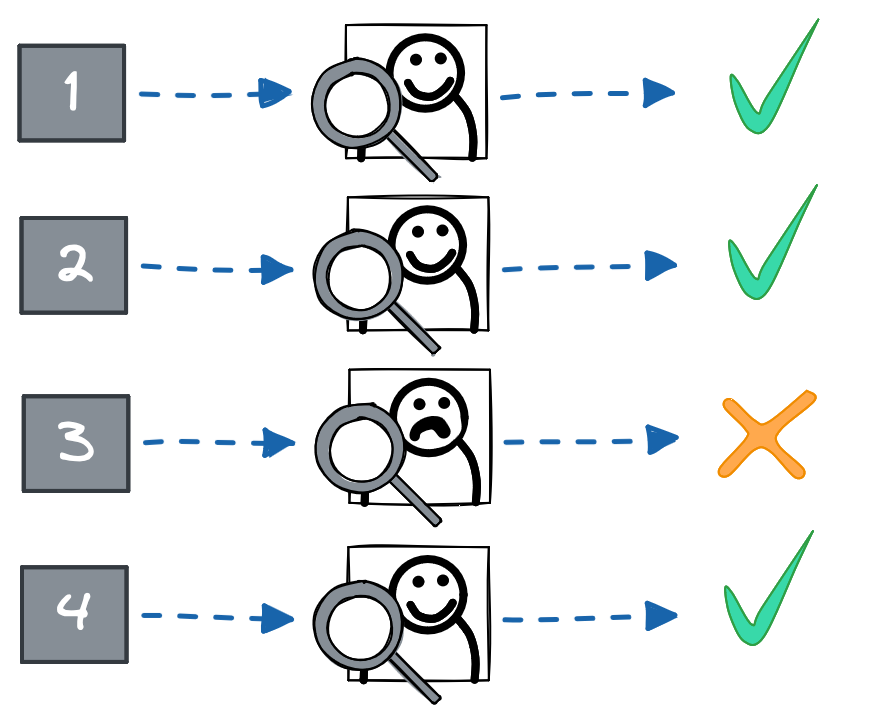

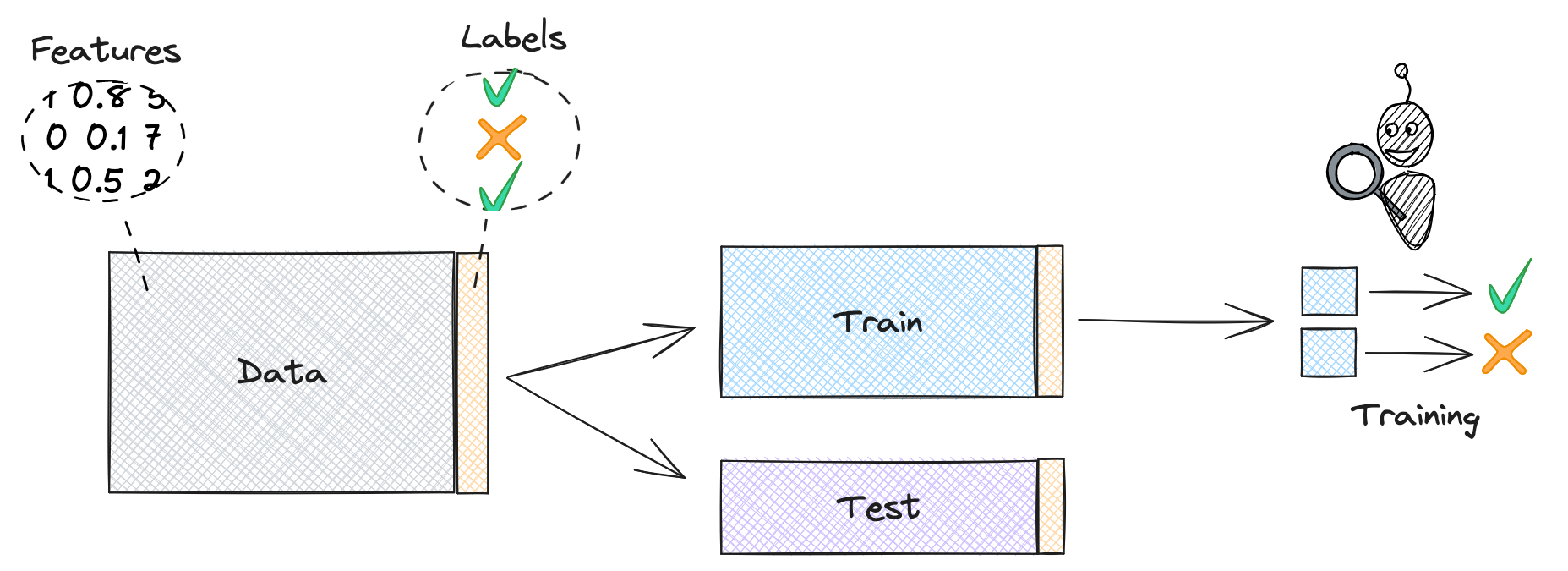

Let’s start with a quick overview of how machine learning classifiers are created and evaluated, using our spam classifier as an example. The first step when training our model is to split our data into train and test sets. An algorithm then parses the training data to learn the relationship between features and labels (spam or benign). The result is a model that can take in the features of a video and return the probability it is spam.

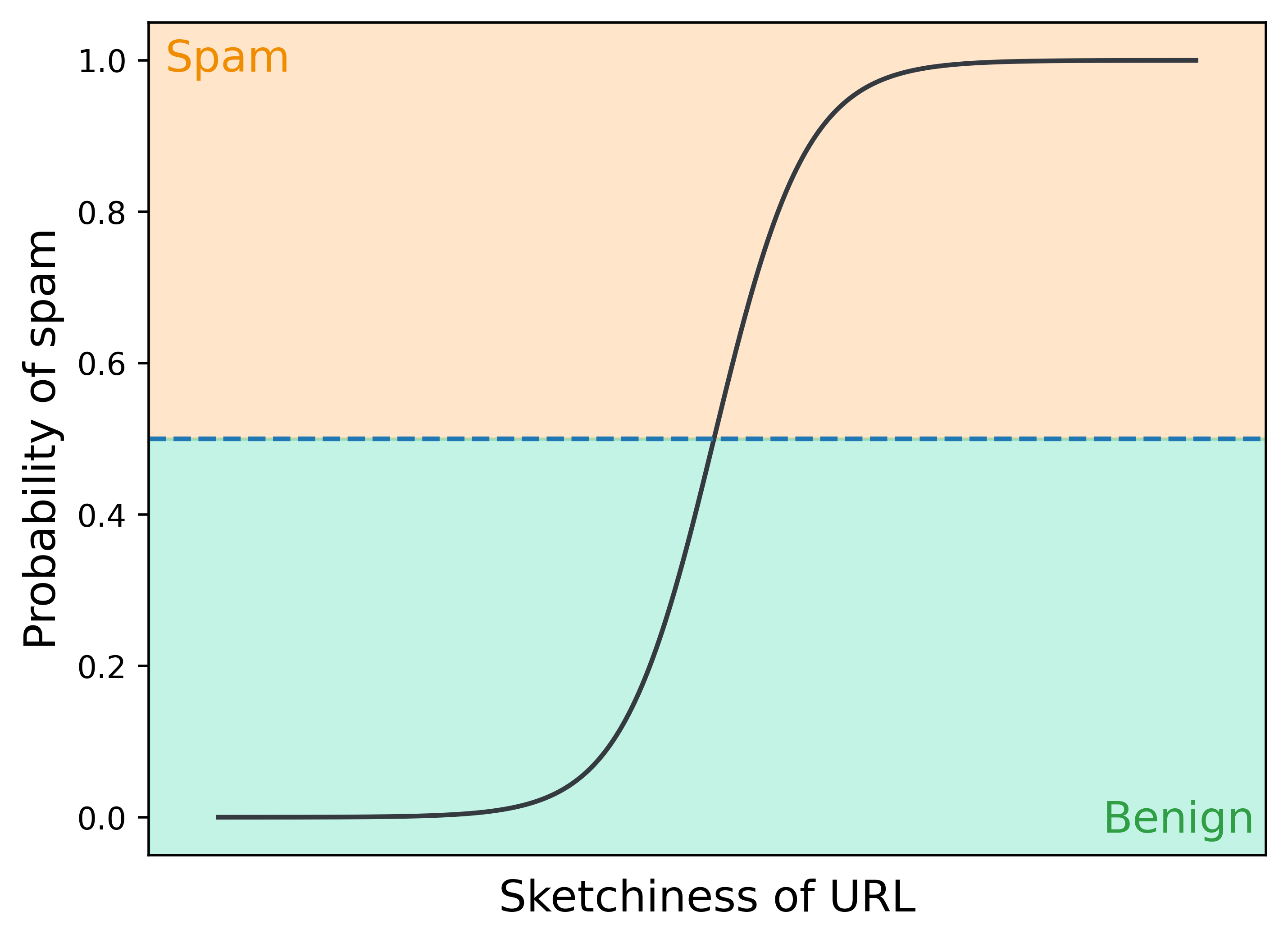

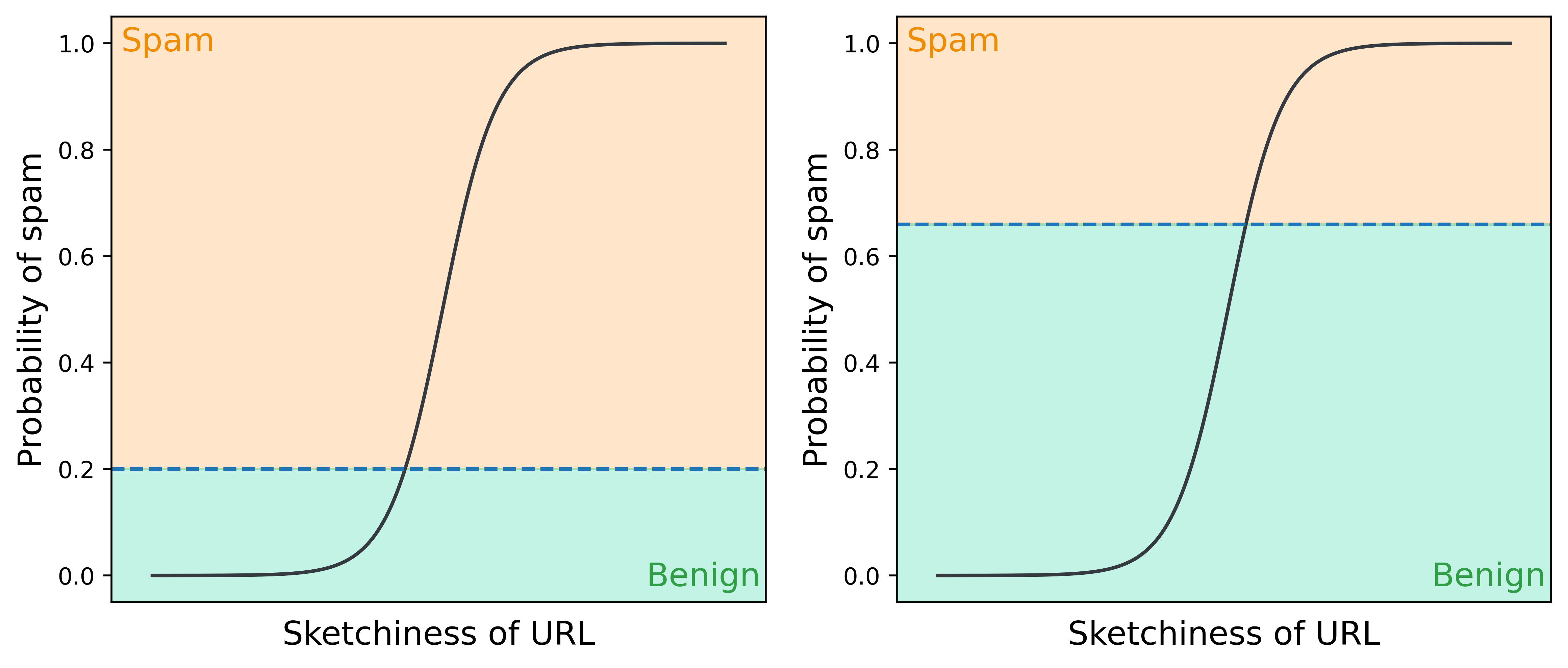

Probabilities are great, but we need some way to convert numbers like 0.17 or 0.55 into a decision on whether a video is spam or not. So we binarize the outputted probabilities – by default at 0.5 – into spam or benign classifications. For an arbitrary feature in our model, the model’s probability curve (black line) and classifications (yellow and green regions) might look like this.

Our model is a best effort at understanding the data it was given. But while understanding the data we have is useful, the real goal is to be able to predict the labels for data we haven’t seen before, like incoming uploaded videos.[4] We measure our model’s ability to do so with the test data: feature-label pairs that weren’t used to train the model. We feed in the features from our test data, see what the model predicts, and compare those predictions to the actual labels. (This is why we don’t train the model on all available data: we need some holdout labels to audit the model’s predictions.)

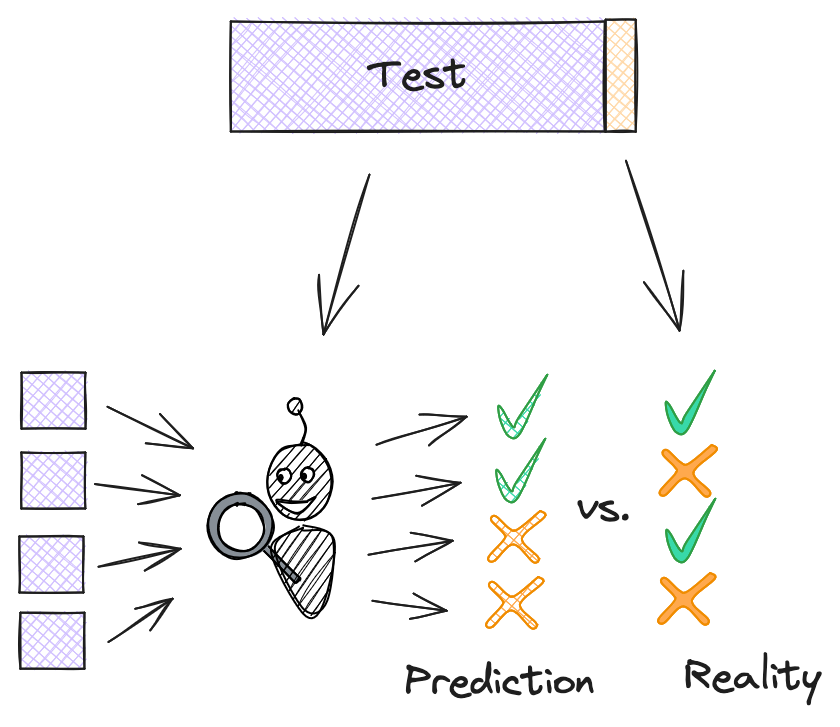

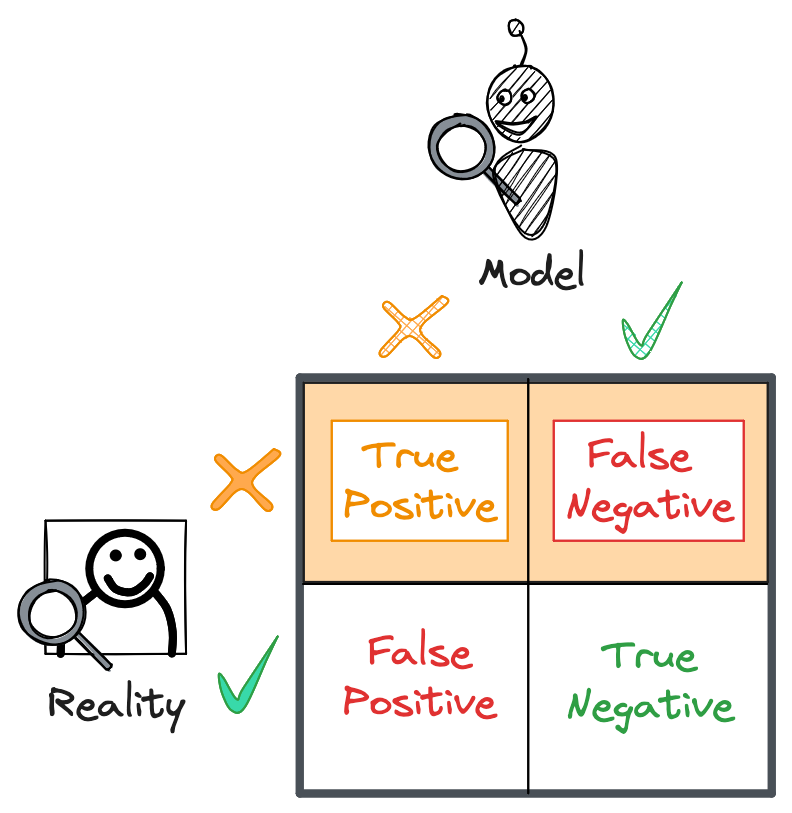

There are four components to measuring our model’s ability to classify new data, based on the four possible outcomes of a prediction:

- True Positive: the model correctly identifies spam.

- False Positive: the model predicts spam, but the video is benign.

- False Negative: the model predicts benign, but the video is spam.

- True Negative: the model correctly identifies a benign video.

We can arrange these outcomes in a confusion matrix. The columns of the matrix are the predicted spam and benign labels, and the rows are the actual spam and benign labels.

We said earlier that our model’s spam probabilities are binarized at 0.5 into spam and benign classifications. But 0.5 isn’t always the best threshold, especially if the data is imbalanced. We could set our threshold to any value between 0 and 1 to better partition our classifications.

These thresholds will generate different confusion matrices, reflecting differing ability of each model to accurately generalize to new data. So how we choose a threshold? To answer this, we’ll need to review a few metrics.

Metric 1: Accuracy

Our first strategy for finding a metric that produces the best model may be to maximize accuracy: our model’s ability to detect true positives (TP) and true negatives (TN). Accuracy, in other words, is the proportion of labels that our model correctly predicted. A model with perfect accuracy would have zero false positives (FP) or false negatives (FN).

\[Accuracy = \frac{TP+TN}{TP+FP+FN+TN}\]Accuracy is an intuitive metric to start with, but it can hide some blindspots in our model. If one label is far more frequent than the other, for example, our model may struggle to predict the less frequent labels or even converge on a nonsensical rule! If our training data was just a random sample of uploaded videos, for example, we may end up with 99.9% benign videos and 0.1% spam. A model that always predicts that a video is benign would be 99.9% accurate. That’s not good at all – we’d miss all the videos we want to catch!

Even with balanced data, we should never rely solely on accuracy when judging a model. Let’s look at other metrics that can give us a more holistic picture.

Metric 2: Recall

To measure how well our model classified the positive samples in the test set, we’ll want to look at our model’s recall. Recall is the proportion of positive labels our model correctly predicted. In other words:

\[Recall = \frac{TP}{TP+FN}\]We can think of this as the top row of the confusion matrix. Recall is the number of true positives divided by the total number of positive labels: labels our model caught (true positives) and missed (false negatives). A model with 100% recall is one that correctly classified all positive labels in the test set.

That 99.9% accurate “always predict benign” model would have zero recall, a glaring red flag indicating the model should be immediately thrown out. Ideally, our model is sensitive enough to catch all spam labels in the test set. But to ensure this sensitivity doesn’t come at the expense of mis-labeling benign videos, we need to look at one more metric: precision.

Metric 3: Precision

When our model classifies a video as spam, how often is it actually spam? This is the core idea behind precision, or the proportion of predicted positive labels that are true positives. As an equation, precision takes the following form:

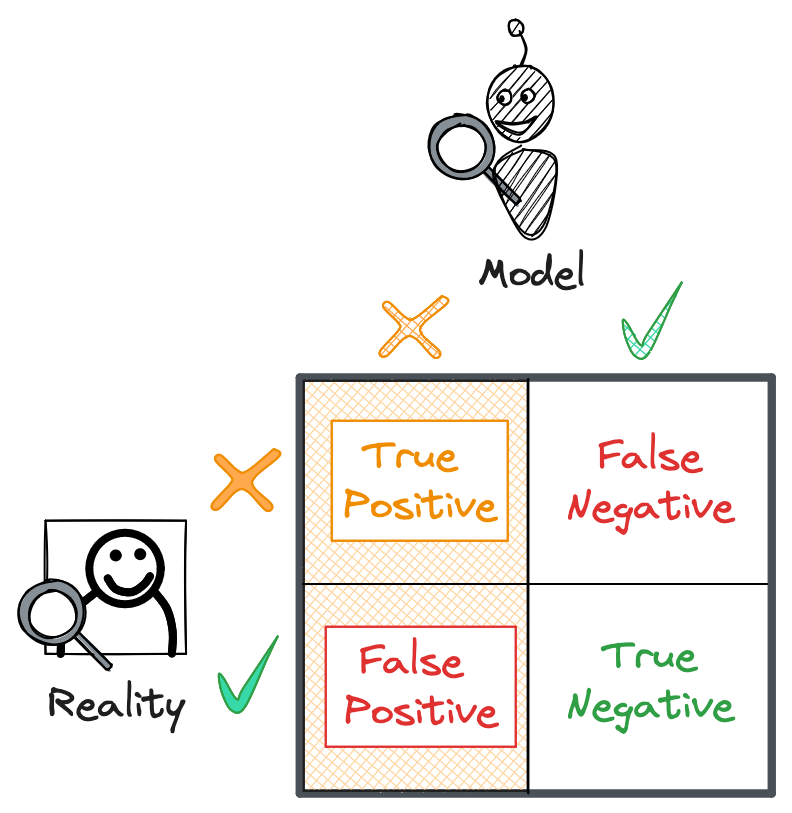

\[Precision = \frac{TP}{TP+FP}\]We can think of this as the left column of the confusion matrix. Precision is the number of true positives divided by the total number of predictions: those that were correct (true positives) and incorrect (false positives).

Precision is a crucial metric for understanding how confident we should be when our model predicts that a video is spam. When a high-precision model predicts that a video is spam, the video is likely spam; if the model has low precision, who knows if it’s actually spam unless we look at it ourselves.

It may therefore be tempting to just optimize for precision, maximizing our confidence in the model’s predictions. But the more we prioritize precision, the more conservative our model will be with labeling videos as spam, meaning we’ll inevitably miss some spam videos that should have been caught.

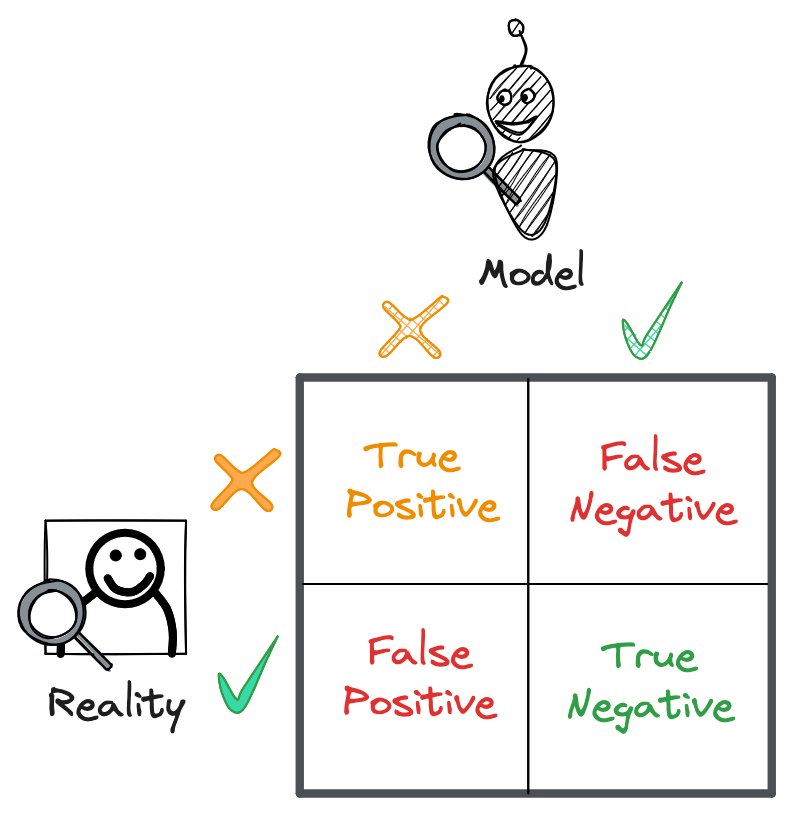

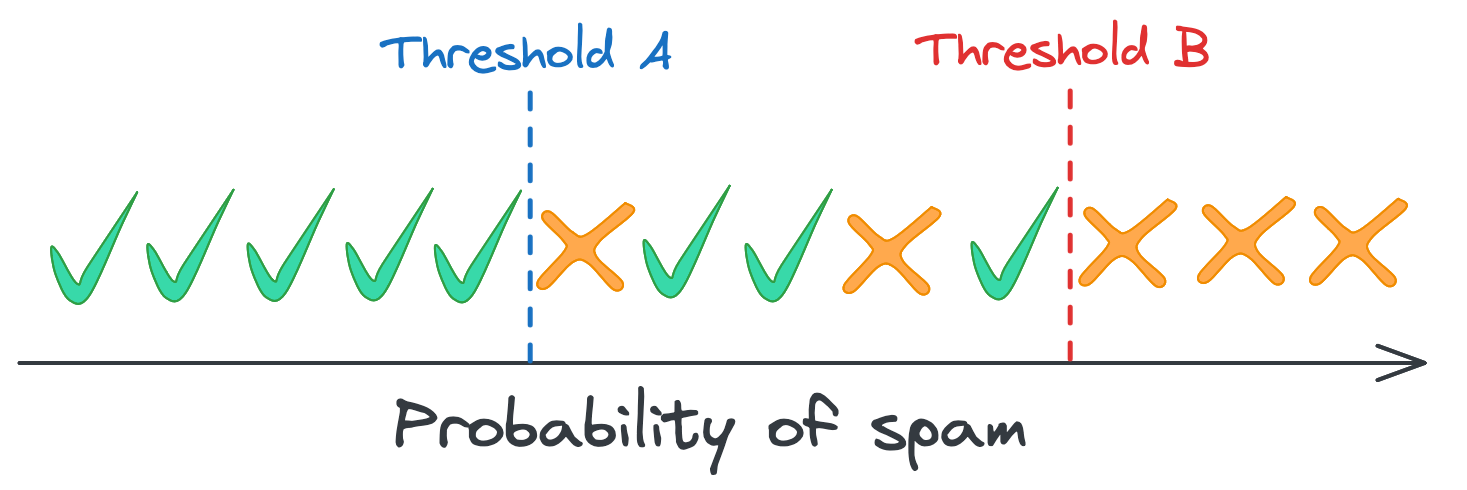

To illustrate this, let’s look at that diagram of the overlap of benign and spam distributions again. We can binarize our spam probabilities at two thresholds: A or B.

Every video to the right of threshold B is spam, so a classifier that binarizes at that spam probability will have 100% precision. That’s impressive, but that threshold misses the two spam videos to the left. Those videos would be incorrectly classified benign (false negatives) because our model isn’t confident enough that they’re spam. Meanwhile, a model whose cutoff is threshold A would catch those spam videos, but it would also mis-label the three benign videos to the right (false positives), resulting in lower precision.

Striking a balance

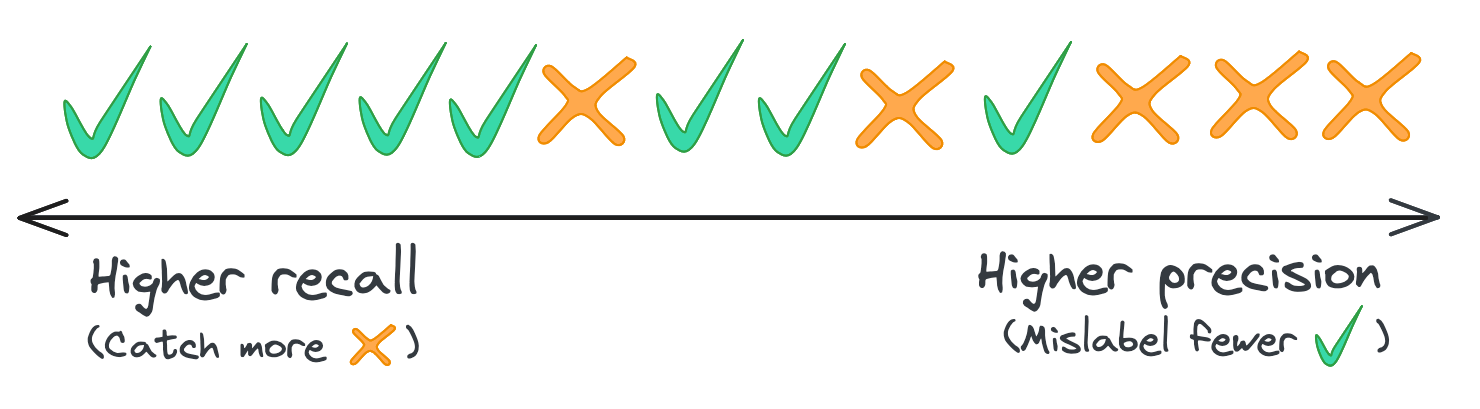

This tradeoff gets at the inherent tension between precision and recall: when we increase our classification threshold, we increase precision but decrease recall. We can redraw our figure to highlight this tradeoff.

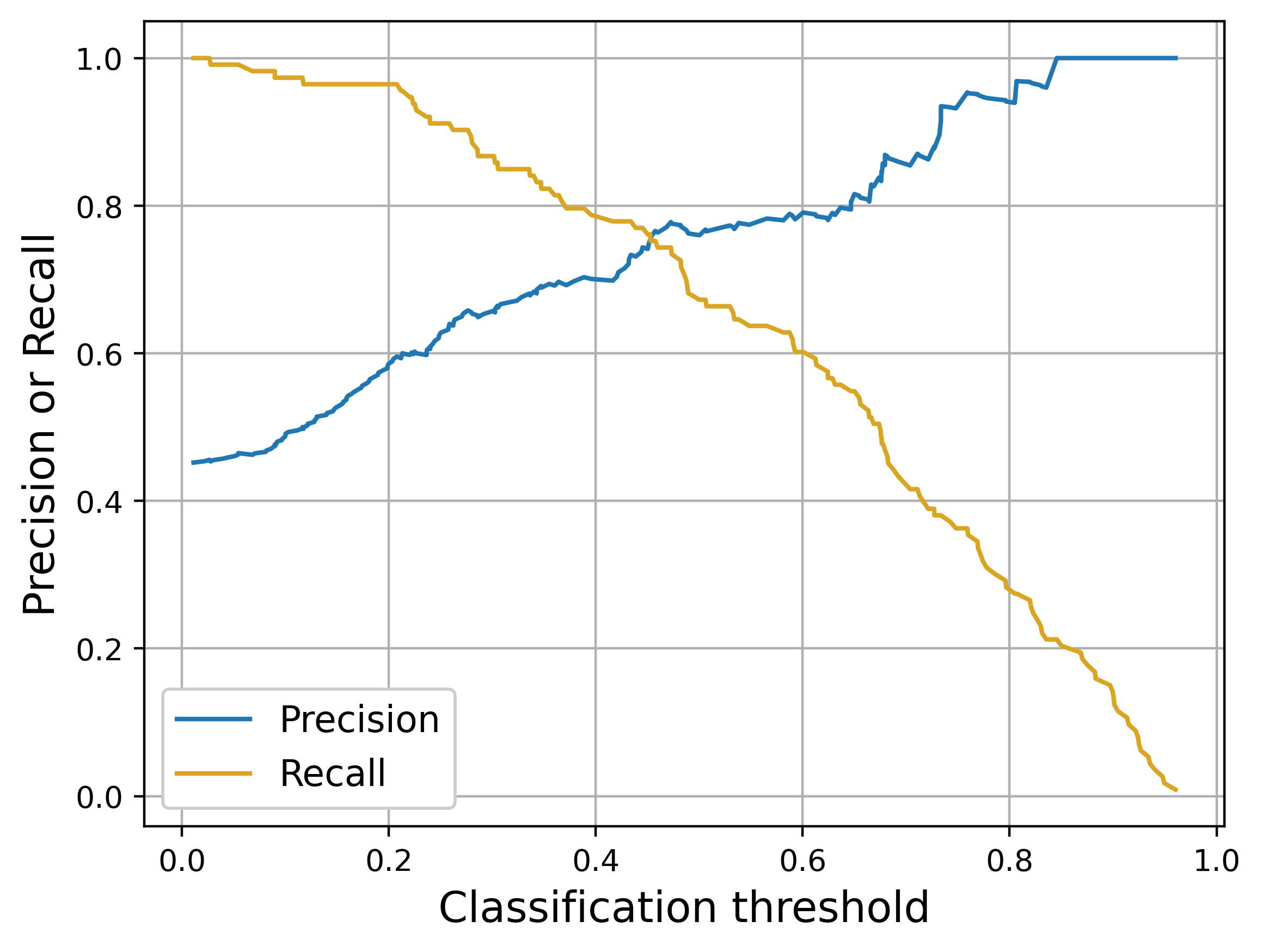

Another way to visualize this is to plot precision and recall as a function of the classification threshold. Using a classifier I trained on some sample data, we can see how precision increases as we increase our threshold but recall steadily decreases. The higher our threshold, the more accurate our model’s predictions become, but also the more spam videos we miss.

So how do we strike a balance? Ultimately, we must ask whether we’re more comfortable with false positives or false negatives, and by how much. Is it worse if some users are incorrectly blocked from uploading videos or if they encounter scams on the platform? Is it worth blocking 100 benign videos to prevent 1 spam video? 1000 benign videos?

Our app’s main selling point was that users would never see spam videos. To achieve 100% recall with our classifier, we’d have to settle for around 45% precision – an embarrassingly imprecise model that would result in thousands of benign videos being blocked daily. If we were comfortable with only catching 90% of spam, we could perhaps get up to 60% precision, but we’d still be blocking far too many videos as well as allowing spam through.

Comparing models

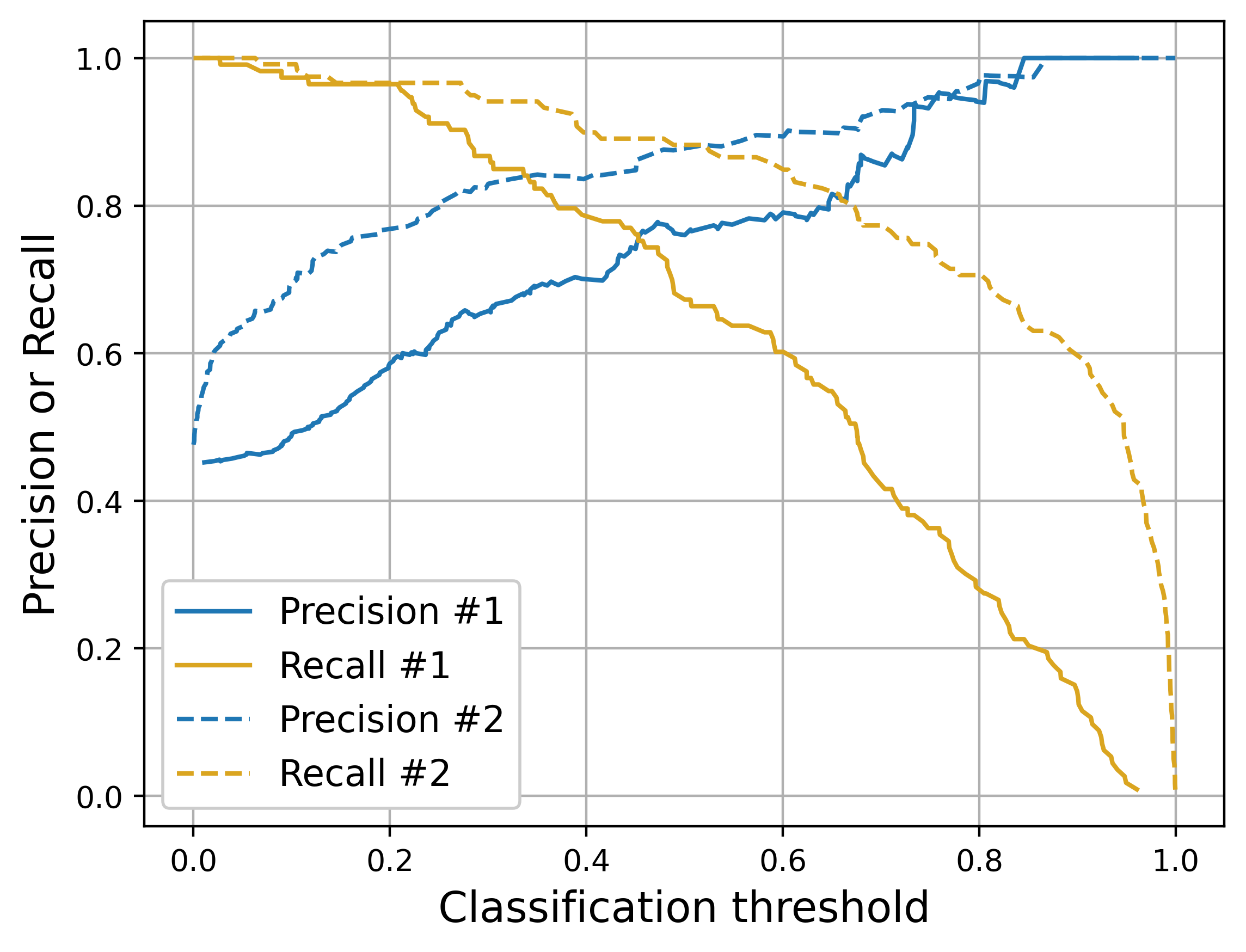

We go back to the drawing board, digging deep into the data to find better features associated with spam. We identify some promising trends and retrain our classifier. When we visualize the precision and recall versus classification threshold for our two models, we see something like the plot below; the solid lines are the old model and the dashed lines are the new.

That’s looking a lot better! For most thresholds, the new model is a huge improvement in both precision and recall, making our tradeoff discussions more palatable. The highest precision we can now get while maintaining 100% recall is roughly 60%. At 90% recall, we have 85% precision.

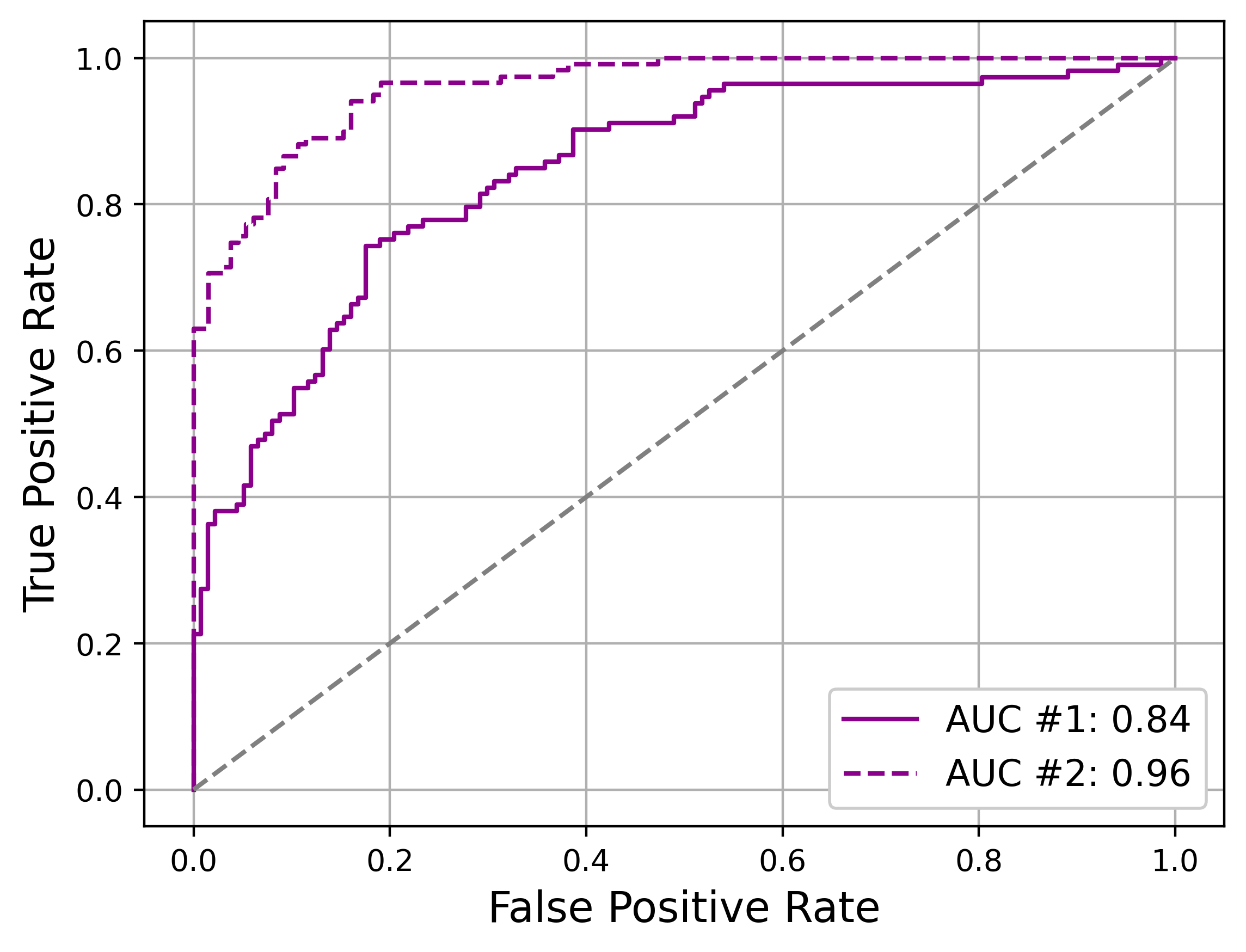

We can summarize our improvement in model fit across all thresholds with AUC-ROC, or the Area Under the ROC (Receiver Operator Characteristic). An ROC curve is a plot of the true positive rate (recall) versus the false positive rate (how often benign videos are flagged as spam). The area under this curve is 1 if our model can perfectly separate benign and spam videos across all thresholds, 0.5 if it is no better than randomly guessing (the gray dashed line below), and somewhere in between otherwise. This one number provides a quick way to show the overall improvement in our new model (AUC = 0.96) compared to the old one (AUC = 0.84).

So by any metric, we can celebrate our improved ability to fight spam with our new classifier. But we’re left looking uncomfortably at our commitment to absolutely zero spam videos on our app. To achieve 100% recall, do we really need to settle for 60% precision, barely better than a coin flip, when classifying videos uploaded to our app? Do we need to go back to model development, or is there anything else we can do?

Back to our App

Attempt 3: Machine Learning + Human Review

If we continue thinking solely in terms of machine learning, we’re going to spend a lot of effort chasing diminishing returns. Yes, we can find better features, algorithms, and hyperparameters to improve model fit. But if we take a step back, we can see that our classifier is really only one part of a funnel for identifying spam, and that we’ll be far more successful investing in the funnel as a whole rather than just the machine learning portion.

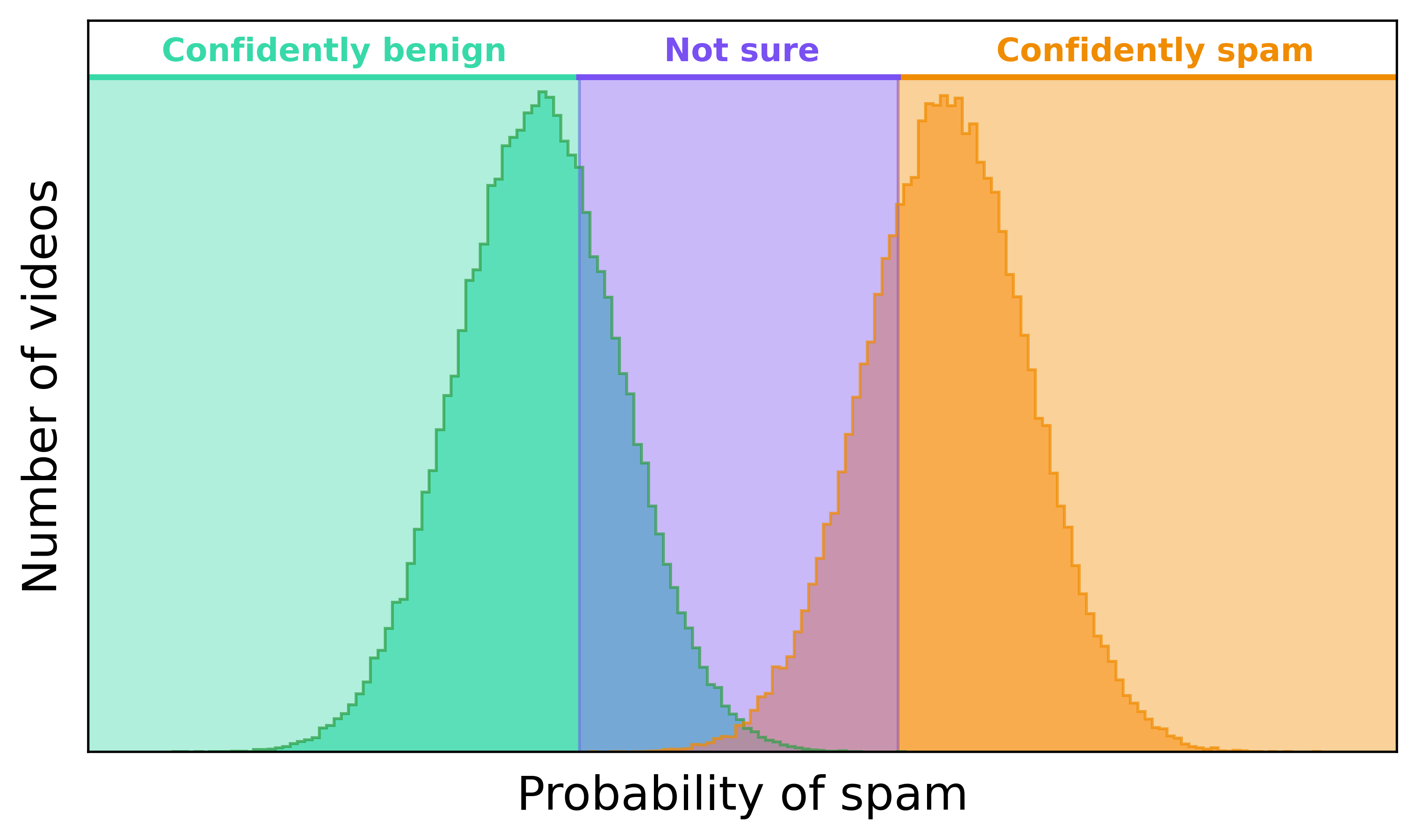

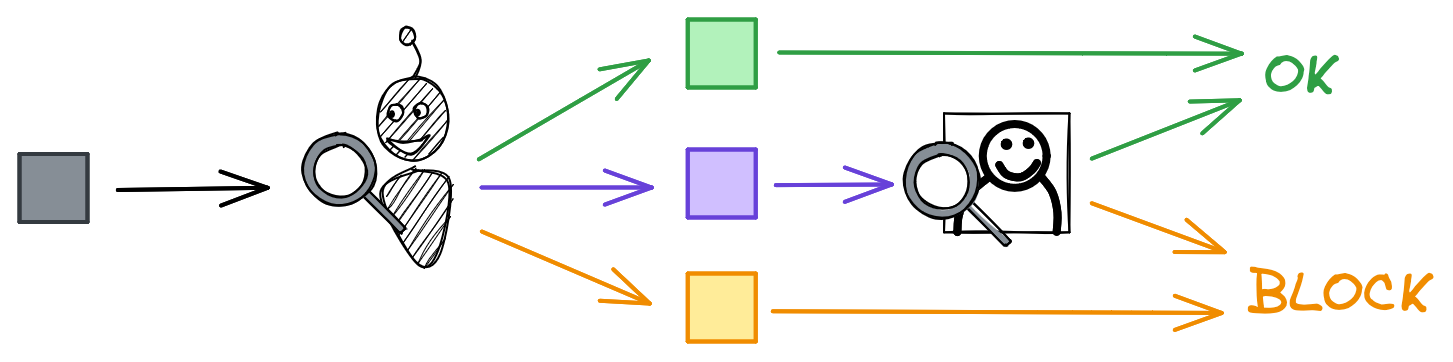

If we revisit our overlapping spam distribution figure from before, we can define three regions of spam probabilities: confidently benign, confidently spam, and “not sure.” We just discussed how to use precision and recall to quantify the tradeoffs of binarizing that uncertainty region into benign and spam. But it doesn’t have to be so black and white if we combine our classifier with those human reviewers from before.

What if instead of wringing our hands trying to find the perfect classification threshold, we instead set thresholds for the boundaries of that purple region above? If our classifier is confident a video is spam or benign, we let it automate that decision for us. But if it’s unsure, we send the video to a human for the final decision.

We now face two precision-recall tradeoffs – the lower and upper thresholds of the uncertainty region – but the stakes for false positives are much lower: rather than risk blocking benign videos outright, we now risk wasting human review capacity. (While inefficient, our reviewers won’t complain if they review some benign videos, whereas users will quit our app if we incorrectly block enough of their videos.)

False negatives (letting a spam video through) are still costly, given our app’s commitment to quality. So as long as we have human review capacity, we can make our uncertainty window as large as possible to ensure as many spam videos are caught as possible. But is this enough to assure that no spam videos make it onto the platform?

Opportunity costs and adversarial actors

The answer, unfortunately, is no. Even when combining the best of machine learning and human review, we cannot prevent 100% of spam from entering the platform.

The first reason, which we covered earlier, is financial. Human review is expensive, and we cannot hire enough people to process all videos with an intermediate spam probability without bankrupting the company. Beyond a certain level of investment, we both catch marginally less spam and cut into funding for other company initiatives such as new features, market expansion, or customer support. There is also plenty of other safety work that needs funding, such as preventing bad actors from hacking or impersonating users. At some point, the opportunity costs of other work are so high that we can actually have a better app overall if we accept some level of spam on the platform.

The second reason we can’t prevent 100% of spam is that our classifier quickly becomes outdated as the spam feature space changes. Spammers are adversarial, meaning they change tactics as soon as companies identify rules to consistently block spam. These bad actors are relentless; scamming people is how they feed their families, and they have infinite motivation to find ways to circumvent our defenses.

Cruelly, the features with the highest predictive power often become irrelevant as spammers investigate why their content is being blocked and then change their approach. The result is a Red Queen arms race between platforms and spammers. If we don’t constantly invest in innovating and iterating how we fight spam, spammers will quickly circumvent our defenses and overrun our platform with junk. But even with a stellar team of engineers and investigators, some spam will make it onto the platform before we can update our systems to catch it.

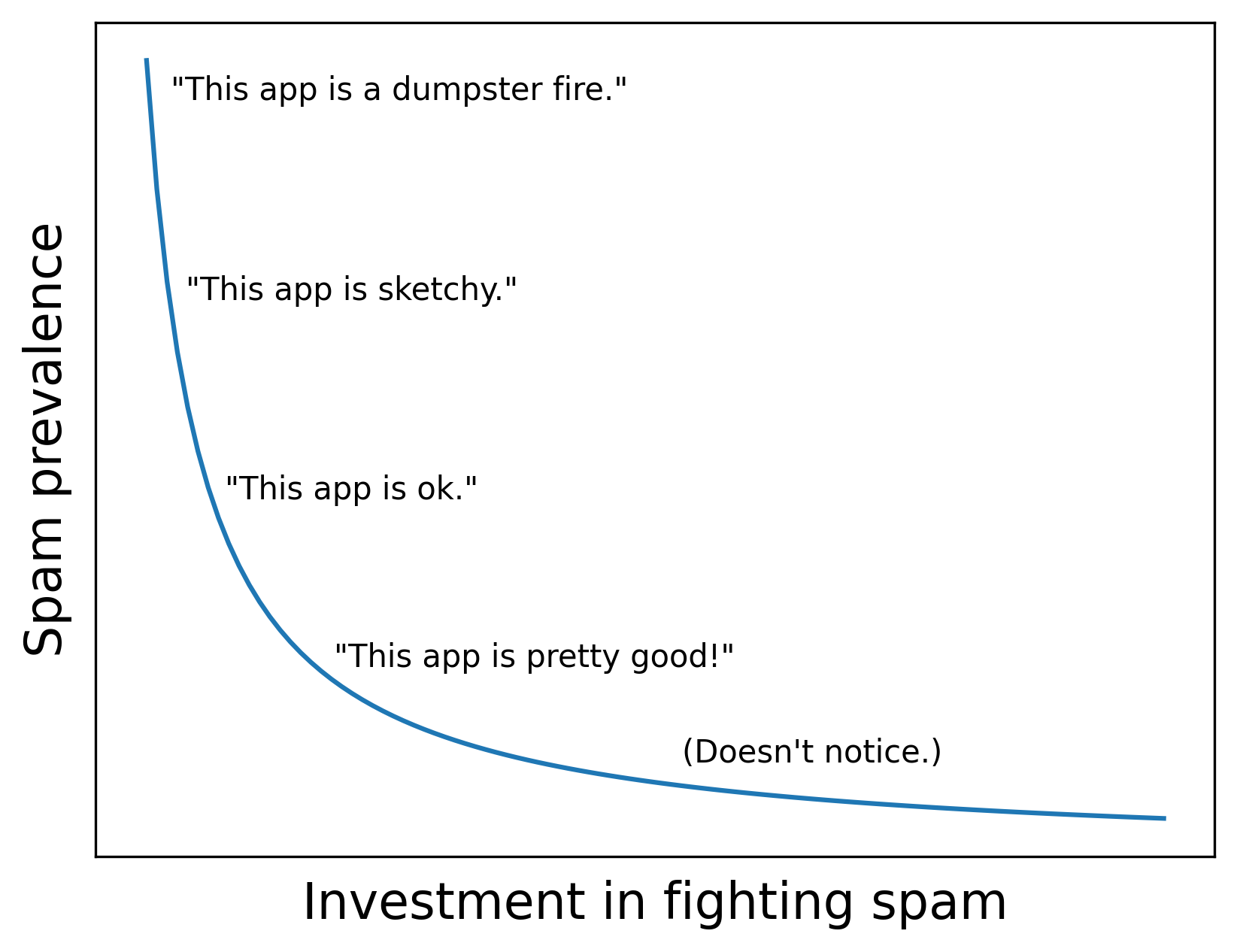

Spam equilibrium

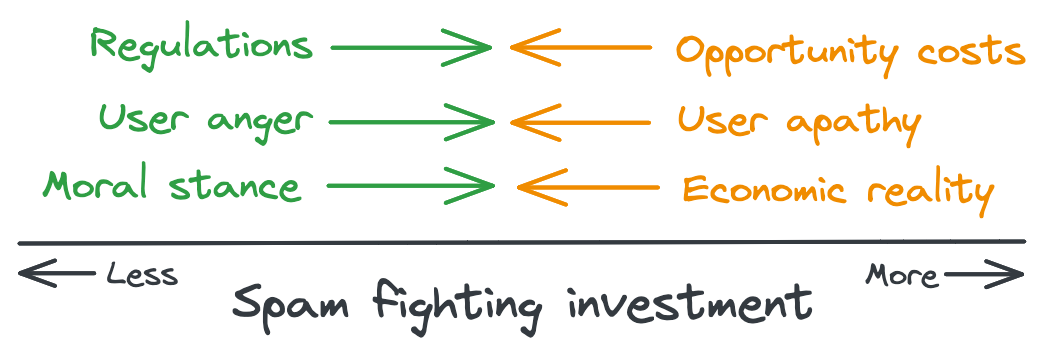

So if we can’t have 0% spam on our platform, where do we end up? The answer to this depends on a number of competing factors.

The first, and potentially strongest force, is regulation. If laws are passed that impose severe financial penalties whenever users get scammed on our app, the investment equilibrium shifts pretty heavily towards minimizing spam. But unless the laws really have some teeth, this force is countered by the opportunity cost of not working on other company initiatives (which themselves may have legal pressure from their own regulations).

The second set of forces comes from users. When spam is noticeable, users get angry; there are viral posts about family members losing life savings, users call on Congress to reign in our company, users leave or boycott our app. So we spend more effort fighting spam, spam prevalence decreases, and users stop complaining. But in the absence of this pressure from users, it can be hard to justify increased investment when no one notices the results.

Finally, there is our company’s internal stance on spam. How much of our company’s maximum possible revenue are we willing to lose if it means investing more in fighting spam than what’s economically optimal? Spam hurts our business, but so does over-investing in fighting it. How far down the diminishing returns are we willing to go based on our moral stance on spam?

Ultimately, the sum of these forces results in some non-zero (and hopefully non-100!) amount of spam on our app. We realize our initial goal with launching our app was naïve given the world we live in. But we decide that’s no reason to give up, so we build a strong anti-spam team, give them the resources they need, and start the never-ending fight for user safety.

Conclusions

This post used the question of “Why is there any spam on social media?” to explore precision, recall, and investment tradeoffs in classification systems. We started by covering different approaches to fighting spam (human review and machine learning) before discussing ways to quantify what we gain and lose when we set classification thresholds. We then discussed the numerous challenges with fighting spam on social media.

Again, this post is solely my opinions and is not commentary on any content policy at any company. Thanks for reading!

Best,

Matt

Code

Below is the code for generating the data and classifier mentioned in this post. The improved classifier was generated by decreasing the standard deviation of the random noise on lines 20 and 21.

| Python |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.metrics import precision_recall_curve

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

# Generate labels

is_spam = np.concatenate(

[

np.random.choice([0, 1], p=[0.9, 0.1], size=200),

np.random.choice([0, 1], p=[0.8, 0.2], size=200),

np.random.choice([0, 1], p=[0.6, 0.4], size=200),

np.random.choice([0, 1], p=[0.4, 0.6], size=200),

np.random.choice([0, 1], p=[0.1, 0.9], size=200),

]

)

# Generate features

feature_1 = [np.random.normal(0, 1.5, 1) if x == 0 else np.random.normal(3, 1.5, 1) for x in is_spam]

feature_2 = [np.random.normal(0, 2.5, 1) if x == 0 else np.random.normal(3, 2.5, 1) for x in is_spam]

df = pd.DataFrame(

{

'is_spam': is_spam,

'feature_1': feature_1,

'feature_2': feature_2,

}

)

############################################################

# Train classifier

X = df[['feature_1', 'feature_2']]

y = df['is_spam']

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y)

mod = LogisticRegression()

mod.fit(X_train, y_train)

############################################################

# Generate predictions

preds = mod.predict_proba(X_test)[:,1]

precision, recall, thresholds = precision_recall_curve(y_test, preds)

df_pred = pd.DataFrame(

{

'precision': precision[:-1],

'recall': recall[:-1],

'threshold': thresholds,

}

)

Footnotes

1. Attempt 1: Human Review

To illustrate how impractical 100% human review is, consider YouTube. Users upload over 500 hours of video every minute, or 1.8 million hours per day. Reviewing this number of videos manually would require 75,000 reviewers watching videos 24/7, or 240,000 if reviewers only work 8-hour shifts and have a lunch break. Add 1,000 to handle re-reviewing videos whose creators claim were incorrectly deleted. We’re left with 241,000 reviewers, or 160% the number of Google employees. That’s not going to work.

2. Attempt 2: Machine Learning

Note that machine learning isn’t the only option for fighting spam. There is a solid use case for hand-crafted deterministic rules for subsets of spam. Something like “how often should a user be allowed to post a video?” probably doesn’t need a dedicated classifier and could be inferred from a distribution of the number of times users post in a day, for example.

3. Attempt 2: Machine Learning

Throughout this post I use the singular “model” or “classifier” to refer to our system for catching spam. But spam is a vast, multi-faceted space, so we probably actually want an ensemble of models, each trained on different subsets of spam. This ensemble approach is how Facebook’s News Feed works. Individual items in Feed are ranked by many models, each outputting a likelihood that a user will like the item, or comment on it, or start following the page that posted the item, etc.

4. Evaluation framework

Modeling just the existing data can be useful, too, but this falls more in the realm of business intelligence or data analytics. The goal there is to understand our data, but there is not necessarily a predictive component of trying to understand future data.