SQL vs. NoSQL databases in Python

#python #sqlWritten by Matt Sosna on April 5, 2021

From ancient government, library, and medical records to present-day video and IoT streams, we have always needed ways to efficiently store and retrieve data. Yesterday’s filing cabinets have become today’s computer databases, with two major paradigms for how to best organize data: the relational (SQL) versus non-relational (NoSQL) approach.

Databases are essential for any organization, so it’s useful to wrap your head around where each type is useful. We’ll start with a brief primer on the history and theory behind SQL and NoSQL. But memorizing abstract facts can only get you so far $-$ we’ll then actually create each type of database in Python to build an intuition for how they work. Let’s do it!

A time series of databases

SQL databases

Databases arrived shortly after businesses began adopting computers in the 1950s, but it wasn’t until 1970 that relational databases appeared. The main idea with a relational database is to avoid duplicating data by storing it only once, with different aspects of that data stored in tables with formal relationships. The relevant data can then be extracted from different tables, filtered, and rearranged with queries in SQL, or Structured Query Language.

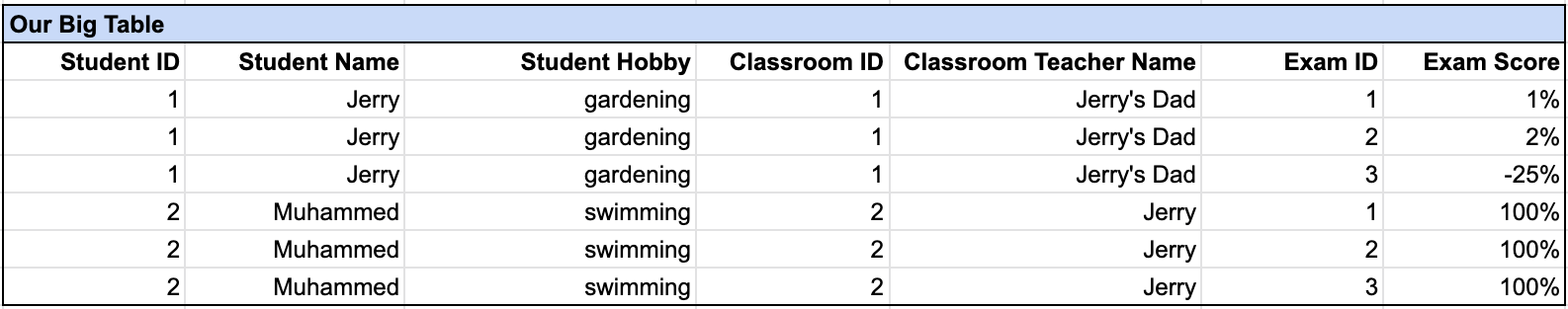

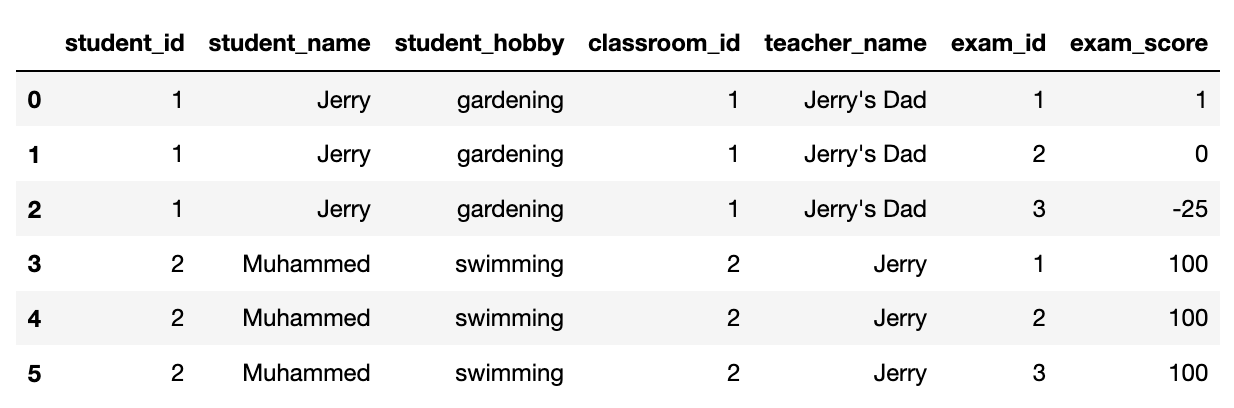

Say we’re a school and are organizing our data on students, grades, and classrooms. We could have one giant table that looks like this:

This is a pretty inefficient way to store data, though. Because students have multiple exam scores, storing all the data in one table requires duplicating info we only need to list once, like Jerry’s hobby, classroom ID, and teacher. If you only have a handful of students, it’s no big deal. But as the amount of data grows, all those duplicated values end up costing storage space and making it harder to extract the data you actually want from your table.

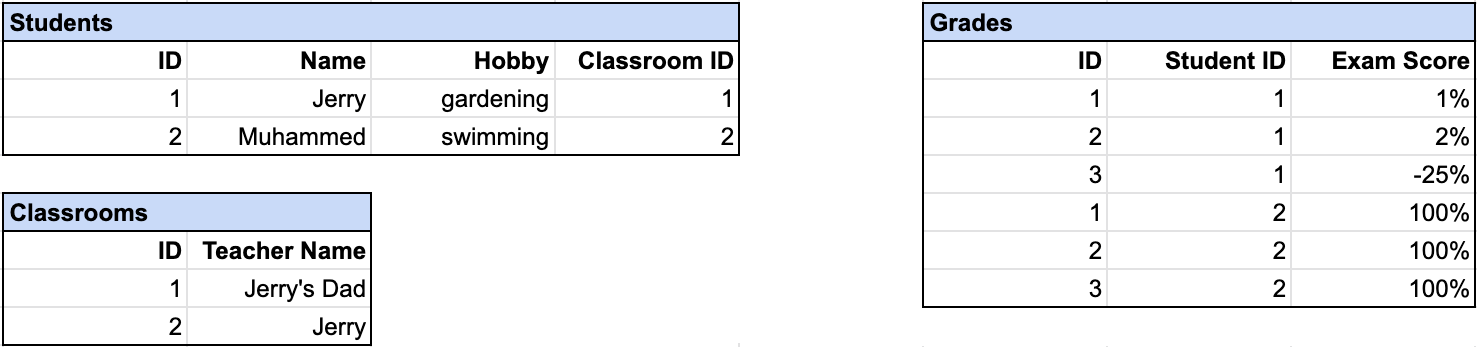

Instead, it’d be far more efficient to break out this information into separate tables, then relate the info in the tables to one another. This is what our tables would look like:

That’s only 30 cells compared to 42 in the main table $-$ a 28.5% improvement! For this particular set of fields and tables, as we increase the number of students, say to 100 or 1,000 or 1,000,000, the improvement actually stabilizes at 38%. That’s more than a third less storage space just by rearranging the data!

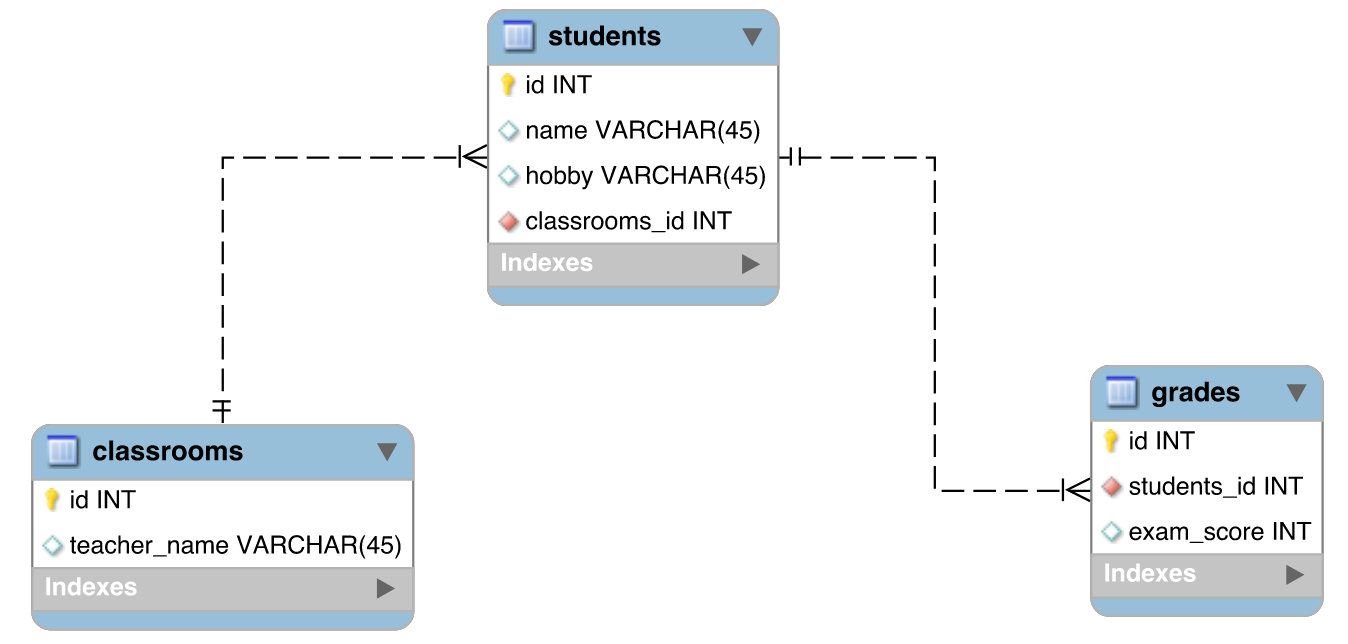

But it’s not enough to just store the data in separate tables; we still need to model their relationships. We can visualize our database schema with an entity-relationship diagram like the one below.

This diagram shows that one classroom consists of multiple students, and each student has multiple grades. We can use this schema to create a relational database in a relational database management system (RDBMS), such as MySQL or PostgreSQL, and then be on our merry, storage-efficient way.

NoSQL databases

So we’ve figured how to solve all data storage problems, right? Well, not quite. Relational databases are great for data that can easily be stored in tables, such as strings, numbers, booleans, and dates. In our database above, for example, each student’s hobby can easily be stored in one cell as a string.

But what if a student has more than one hobby? Or what if we want to keep track of subcategories of hobbies, like exercise, art, or games? In other words, what if we want to store values like these:

1

2

3

hobby_list = ['gardening', 'reading']

hobby_dict = {'exercise': ['swimming', 'running'],

'games': ['chess']}

To allow for lists of hobbies, we could create an intermediary many-to-many table to allow students to have multiple hobbies (and for multiple students to have the same hobby). But it starts getting complicated for the hobby dictionary… we’d probably need to store our dictionary as a JSON string, which relational databases are really not built for.[1]

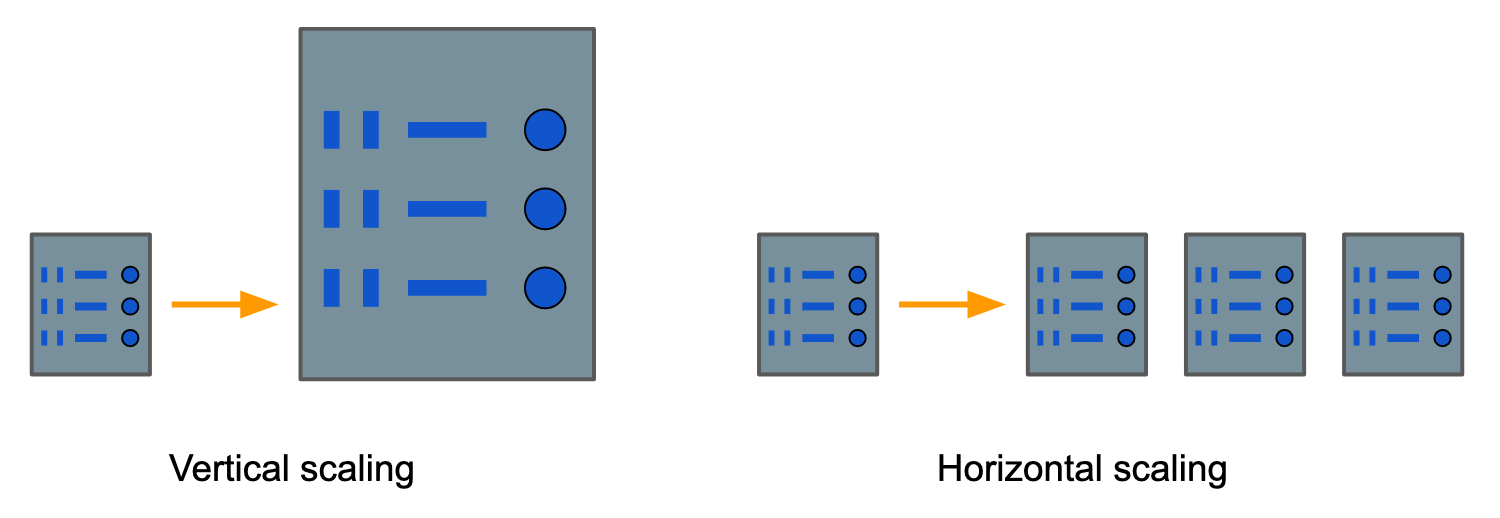

Another issue with relational databases appeared in the 90’s as the internet grew in popularity: how to handle terabytes and petabytes of data (often JSON) with only one machine. Relational databases were designed to scale vertically: when needed, configure more RAM or CPUs to the server hosting the database.

But there comes a point where even the most expensive machine can’t handle a database. A better approach may be scale horizontally: to add more machines rather than try to make your one machine stronger. This is not only cheaper $-$ it bakes in resilience in case your one machine fails. (Indeed, distributed computing with cheap hardware is the strategy Google used from the start.)

NoSQL databases address these needs by allowing for nested or variable-type data and running on distributed clusters of machines.[2] This design enables them to easily store and query large amounts of unstructured data (i.e. non-tabular), even when records are shaped completely differently from one another. Muhammed have a 50-page JSON of neatly-organized hobbies and sub-hobbies while Jerry only enjoy gardening? No problem.

But of course, this design also has its drawbacks, or we’d have all switched over. The lack of a database schema means there’s nothing stopping a user from writing in garbage (e.g. accidentally writing a “name” string to the “grade” field), and it can be difficult to join data between different collections in the database. Using distributed servers also means queries can return stale data before updates are synchronized.[3] The right choice between a SQL and NoSQL database, then, depends on which of the drawbacks you’re willing to deal with.

Playtime

Enough theory; let’s actually create each type of database in Python. We’ll use the sqlalchemy library to create a simple SQLite database, and we’ll use pymongo to create a MongoDB NoSQL database. Make sure to install sqlalchemy and pymongo to run the code below, as well as start a MongoDB server.

SQL

In professional contexts, we’ll probably want to create a database via a dedicated RDBMS with actual SQL code. But for our simple proof of concept here, we’ll use SQLAlchemy.

SQLAlchemy lets you create, modify, and interact with relational databases in Python via an object relational mapper. The main idea to wrap your head around is that SQLAlchemy uses Python classes to represent database tables. Instances of a Python class can be considered rows of a table.

We start by loading in the necessary sqlalchemy classes. The imports in line 1 are for establishing a connection to the database (create_engine) and defining the schema of our tables (Column, String, Integer, ForeignKey). The next import, Session, lets us read and write to our database. Finally, we use declarative_base to create a template Python class whose children will be mapped to SQLAlchemy tables.

| Python |

1

2

3

4

5

6

from sqlalchemy import create_engine, Column, String, Integer, ForeignKey

from sqlalchemy.orm import Session

# Use the default method for abstracting classes to tables

from sqlalchemy.ext.declarative import declarative_base

Base = declarative_base()

We now create our classroom, student, and grade tables as the Python classes Classroom, Student, and Grade. Note that they all inherit from the Base SQLALchemy class. Our classes are straightforward: they only define their corresponding table name and its columns.

| Python |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

class Classroom(Base):

__tablename__ = 'classroom'

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

teacher_name = Column(String(255))

class Student(Base):

__tablename__ = 'student'

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

name = Column(String(255), nullable=False)

hobby = Column(String(255))

classroom_id = Column(Integer, ForeignKey(Classroom.id))

class Grade(Base):

__tablename__ = 'grade'

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True)

exam_id = Column(Integer)

student_id = Column(Integer, ForeignKey(Student.id))

exam_score = Column(Integer)

Now we create our database and tables. create_engine launches a SQLite database,[4] which we then turn on. Line 4 starts our session and line 7 creates database tables from our Python classes.

| Python |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

# Create DB connection

engine = create_engine("sqlite:///students.sqlite")

conn = engine.connect()

session = Session(bind=engine)

# Create metadata layer that abstracts our SQL DB

Base.metadata.create_all(engine)

We now generate our data. Instances of Classroom, Student, and Grade serve as rows in each table.

| Python |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

classroom1 = Classroom(teacher_name="Jerry's Dad")

classroom2 = Classroom(teacher_name="Jerry")

jerry = Student(name='Jerry', hobby='gardening', classroom_id=1)

muhammed = Student(name='Muhammed', hobby='swimming', classroom_id=2)

exam_j1 = Grade(exam_id=1, student_id=1, exam_score=1)

exam_j2 = Grade(exam_id=2, student_id=1, exam_score=0)

exam_j3 = Grade(exam_id=3, student_id=1, exam_score=-25)

exam_m1 = Grade(exam_id=1, student_id=2, exam_score=100)

exam_m2 = Grade(exam_id=2, student_id=2, exam_score=100)

exam_m3 = Grade(exam_id=3, student_id=2, exam_score=100)

Now we finally write our data to the database. Similarly to Git, we use session.add to add each row to the staging area and session.commit to actually write the data.

| Python |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

objects = [classroom1, classroom2, jerry, muhammed,

exam_j1, exam_j2, exam_j3, exam_m1, exam_m2, exam_m3]:

for obj in objects:

session.add(obj)

# Commit changes to database

session.commit()

Nice work! Let’s wrap up this section by recreating the first table in this post.

| Python |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

import pandas as pd

query = """

SELECT s.id AS student_id,

s.name AS student_name,

s.hobby AS student_hobby,

c.id AS classroom_id,

c.teacher_name,

g.exam_id,

g.exam_score

FROM student AS s

INNER JOIN grade as g

ON s.id = g.student_id

INNER JOIN classroom as c

ON c.id = s.classroom_id;"""

pd.read_sql_query(query, session.bind)

NoSQL

Now let’s switch to MongoDB. Make sure to install MongoDB and launch a local server. Below, we import pymongo, connect to our local server, and then create a database called classDB.

| Python |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

import pymongo

# Establish connection

conn = "mongodb://localhost:27017"

client = pymongo.MongoClient(conn)

# Create a database

db = client.classDB

In a relational database, we create tables with records. In a NoSQL database, we create collections with documents. Below, we create a collection called classroom and insert dictionaries with each student’s info.

| Python |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

db.classroom.insert_many(

[

{

'name': 'Jerry',

'hobbies': 'gardening',

'classroom_teacher': "Jerry's Dad",

'exam_scores': [1, 0, -25]

},

{

'name': 'Muhammed',

'hobbies': {'exercise': ['swimming', 'running'],

'games': 'chess'},

'classroom_teacher': 'Jerry',

'exam_scores': [100, 100, 100]

}

])

Notice how the datatypes in hobbies are different: it’s a string for Jerry and a dictionary for Muhammed. (And even within the hobbies dictionary, the values are both lists and strings.) MongoDB doesn’t care $-$ there’s no schema to enforce datatypes or structure on the data.

We can view our data by iterating through the objects returned from db.classroom.find. We use pprint to make it easier to read the output. Notice how MongoDB adds a unique object ID to each document.

| Python |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

import pprint

classroom = db.classroom.find()

for student in classroom:

pprint.pprint(student)

print()

# {'_id': ObjectId('606b608f07fe3f5be3d00efd'),

# 'name': 'Jerry',

# 'hobbies': 'gardening',

# 'classroom_teacher': "Jerry's Dad",

# 'exam_scores': [1, 0, -25]}

# {'_id': ObjectId('606b608f07fe3f5be3d00efe'),

# 'name': 'Muhammed',

# 'hobbies': {'exercise': ['swimming', 'running'], 'games': 'chess'},

# 'classroom_teacher': 'Jerry',

# 'exam_scores': [100, 100, 100]}

We can easily add a document with new fields.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

import datetime as dt

db.classroom.insert_one(

{

'name': 'Samantha',

'birthday': dt.datetime(2012, 2, 29),

'favorite_color': None

}

)

Finally, let’s perform two queries that really highlight how our MongoDB database differs from SQLite. The first query embraces the lack of a database schema by finding all documents that contain a birthday field. The second query searches for documents that have running in the nested field exercise within hobbies.

| Python |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

for student in db.classroom.find({'birthday': {'$exists': True}}):

pprint.pprint(student)

# {'_id': ObjectId('606b893307fe3f5be3d00f04'),

# 'birthday': datetime.datetime(2012, 2, 29, 0, 0),

# 'favorite_color': None,

# 'name': 'Samantha'}

for student in db.classroom.find({'hobbies.exercise': 'running'}):

pprint.pprint(student)

# {'_id': ObjectId('606b891107fe3f5be3d00f03'),

# 'classroom_teacher': 'Jerry',

# 'exam_scores': [100, 100, 100],

# 'hobbies': {'exercise': ['swimming', 'running'], 'games': 'chess'},

# 'name': 'Muhammed'}

Conclusions

This post covered the history of SQL and NoSQL databases and their relative advantages and disadvantages. We then made things more concrete by creating databases of each type in Python with SQLAlchemy and MongoDB. I highly recommend getting your hands dirty with concepts that are fairly theoretical like the SQL vs. NoSQL battle $-$ I learned a lot from writing the code for this post! Look out for a future post with some coding bloopers, where I’ll explore some limits of SQLite and MongoDB.

Best,

Matt

Footnotes

1. NoSQL databases

This great answer on Stack Overflow explains that relational databases struggle with JSON for two main reasons:

- Relational databases assume the data within them is well-normalized. The query planner is better-optimized when looking at columns than JSON keys.

- Foreign keys between tables can’t be created on JSON keys. To relate two tables, you have to use values in a column, which here would be the entire JSON in the row, rather than keys within the JSON.

2. NoSQL databases

I found it hard to have a short, snappy description for how NoSQL databases store data, since there are multiple NoSQL database types. A key-value database can have virtually no restrictions on its data, a document database has basic assumptions on the format of its contents (e.g. XML vs. JSON), while a graph database may be strict on how nodes and edges are stored. A column-oriented database, meanwhile, effectively consists of tables but with data organized by columns rather than by rows.

3. NoSQL databases

Because a NoSQL database is distributed on multiple servers, there is a slight delay before a change in the database on one server is reflected in all other servers. This usually isn’t an issue, but you can imagine a scenario where someone is able to withdraw money from a bank account twice before all servers are aware of the first withdrawal.

4. SQL

One really nice feature of SQLAlchemy is how it handles differences in SQL syntax for you. We use a SQLite database in this post, but we can switch to MySQL or Postgres just by changing the string we pass into create_engine. All other code remains exactly the same. A nice strategy for writing a Python app that uses SQLAlchemy is to start with SQLite while you’re writing and debugging, and then just switch to something production-ready like Postgres when you deploy.