3 levels of technical abstraction when sharing your code

#computer-scienceWritten by Matt Sosna on April 13, 2021

I’ve been programming now for eight years, and it wasn’t until just months ago that I was able to answer a question I’ve had this whole time: “How do I share my project with someone?”

When I say “project,” I’m not talking about a single R script or a handful of bash commands $-$ even 22-year old me could figure out copy and paste! I mean a project that has several files, perhaps in multiple languages, with external dependencies. Do I just throw it all into a zip folder? How do I deal with new versions of languages and packages that aren’t backwards-compatible? What if the person I’m sharing with doesn’t know how to code at all?

The right way to share your project depends on how much code you want your recipient to see, and how much to abstract away. This post will cover three levels of abstraction: GitHub, Docker, and Heroku. We’ll start with sharing the raw files and end with hiding nearly everything.

Level 1: GitHub

What your recipient needs to do: ensure their computer has the appropriate languages and packages, in the correct versions, that work for their operating system; actually know what code to execute to launch your app.

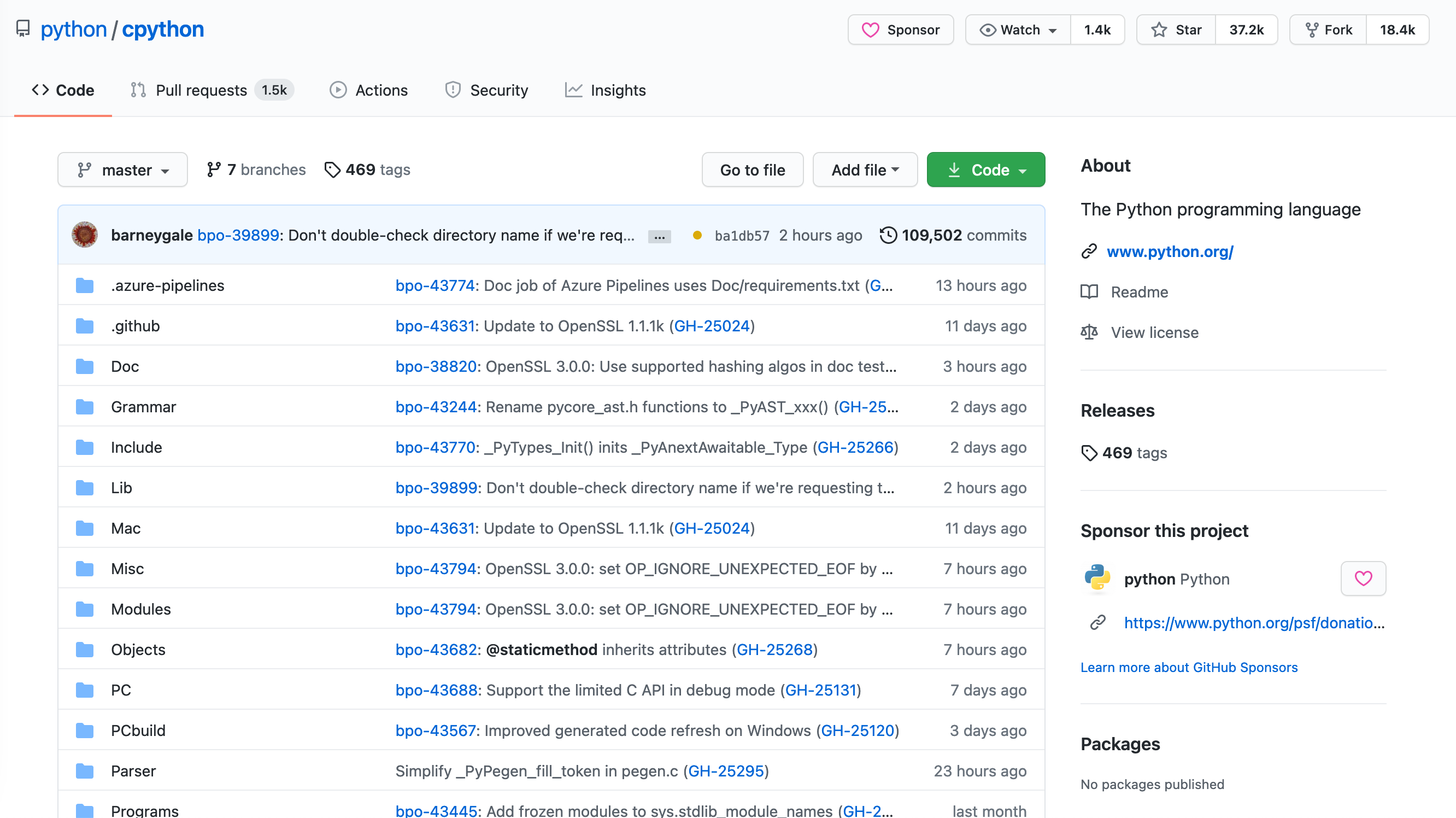

GitHub is the industry standard for hosting your code, tracking changes to it, and sharing it with others. By sending someone a URL to your repository, they can view your code, see the history of changes, save the code to their computer, and submit changes to you for approval.

Sharing code via GitHub is the least abstract of our three options $-$ your recipient gets the raw code itself. While this is great for getting another pair of eyes on the inner workings of your project, a GitHub repo by itself is actually pretty bare-bones for using your code. Without detailed instructions, your recipient may have no idea what your code is supposed to do or how to actually run it!

For example, take a look at the GitHub repo for Python (yes, the Python). Just looking at the files and folders, do you have any idea what commands to type to install Python? (Thankfully, their README has detailed instructions!)

Aside from instructions on how to launch the project, it’s also critical to list the external dependencies (e.g. Python libraries) and their versions. Even though you’re sharing the raw code when you send someone a GitHub repo, your project likely still won’t work on their computer if your code references libraries your recipient doesn’t have installed.

That’s why it’s critical to provide instructions for how to recreate the environment on your computer. In fact, Python-based projects almost invariably start with the user creating a virtual environment and installing the libraries provided in a requirements.txt file.

But even detailed instructions and a requirements.txt file may fall short if your project involves multiple languages and a database. This sample repo for a vote tallying app, for example, involves Python, Node.js, Redis, Postgres, and .NET. If you’re willing to hide some of the code to make it easier to use your app, it may be worth moving to the next level of abstraction: Docker.

Level 2: Docker

What your recipient needs to do: have Docker installed, pull the relevant images, and run a Docker Compose.

Docker is a containerization service. A container is an isolated software environment, where its libraries, programs, and even operating system are independent from the rest of your computer. Think of a Docker container as a miniature computer inside your computer.[1]

With Docker, you can isolate parts of your project $-$ such as the machine learning model vs. the database vs. the email alerts $-$ into independent containers with environments tailored exactly to what that component needs. You can then run these containers in parallel as if they were on the same computer.

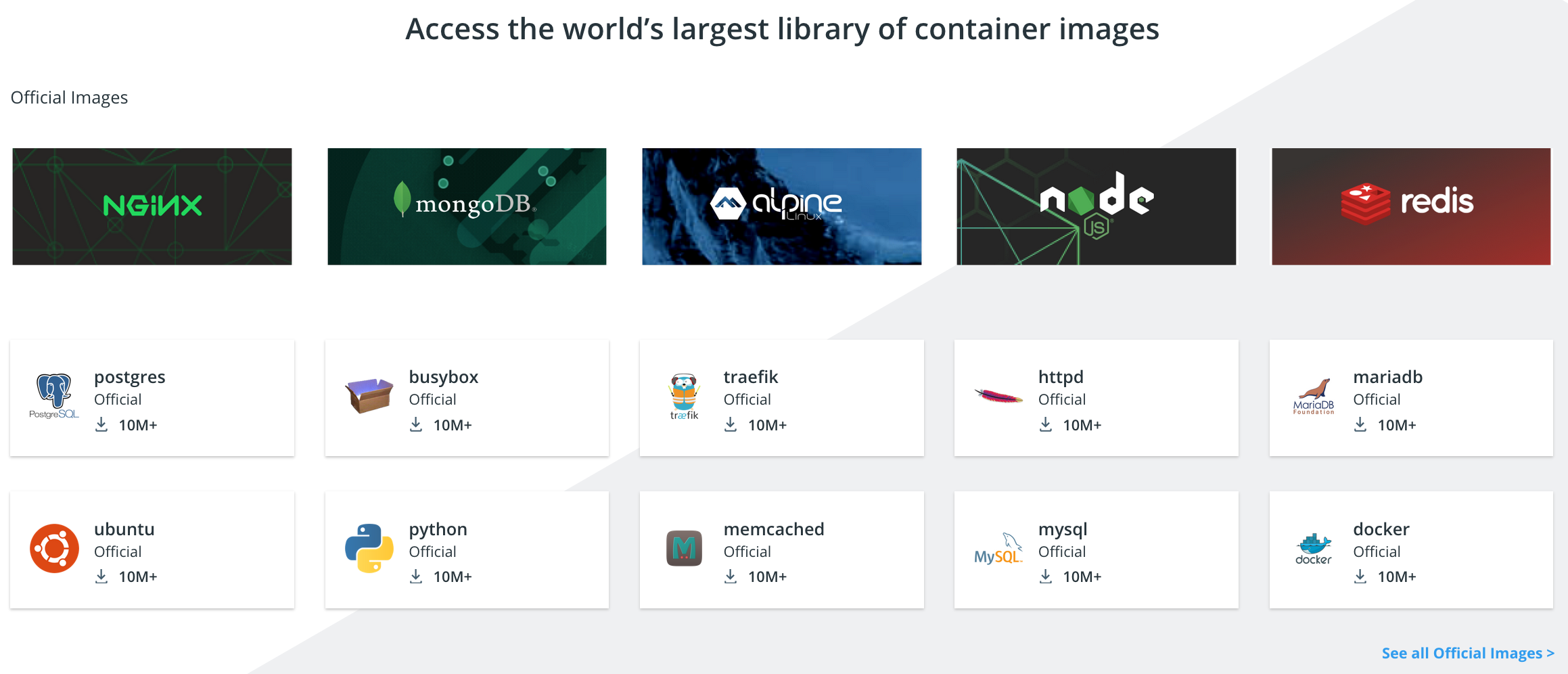

Containers come from publicly-available software “snapshots,” or images, on Docker Hub. If your app only runs on Python2, for example, rather than go through the headache of convincing your recipient to downgrade their Python, just have them download a Python2.7 Docker image.

As of April 2021, there are over 5.8 million images on Docker Hub that you can download for free. And there’s no cost to experimentation: any images you download are quietly hidden from your computer’s global environment until you call on them to create a container.

Even better, though, you can create your own images.[2] The code below is all you’d need to create a Docker image for a simple Flask app. The steps involve installing the Ubuntu operating system, Python, and Flask; copying your app.py file into the container; and making the container accessible to your computer’s internal network.

| Dockerfile |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

# Use the Ubuntu OS Docker image

FROM ubuntu

# Update the Ubuntu packages

RUN apt-get update

# Install Python3, pip, and Flask

RUN apt-get install -y python3 python3-pip

RUN python3 -m pip install flask

# Copy the local app.py file to the Docker image directory

COPY app.py /opt/app.py

# Expose port 80 from the Docker container to the host

EXPOSE 80

# Run this code when container starts

ENTRYPOINT python3 /opt/app.py

To bundle multiple images together, you run a Docker Compose. Here’s what a Compose file looks like for bundling your Flask app with a Postgres database.

| YAML |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

version: "3"

services:

db:

image: postgres:9.4

environment:

POSTGRES_USER: "postgres"

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: "postgres"

flask:

image: my-flask-app

ports:

- 5000:80

With Docker, we can simply send our recipient some Docker images and a Docker Compose file, tell them to run docker compose up, then navigate to a URL in their browser (e.g. http://localhost:5000). That’s it. The user can look at the Compose file to see which services are being used (e.g. whether we’re using a Postgres vs. MySQL database), but otherwise most of the code is kept out of their way.

Level 3: Heroku

What your recipient needs to do: click on a URL.

For our final level of abstraction, we remove all code. No GitHub repos, no command lines. When you host your app on a service like Heroku, AWS, or DigitalOcean, a server in a data center somewhere takes care of running your app. Your user, then, only needs to click on a URL that will take them to that server.

In this level of abstraction, all your user sees is your app’s frontend $-$ typically a graphical interface.[3] Below, for example, is a screenshot from a spam catching app I wrote. Aside from the HTML and CSS on the webpage, you can’t tell what’s happening behind the scenes. (Unless you go the GitHub repo or read the blog series I wrote. ;-))

If your app’s frontend code is written well, even a crafty user won’t be able to tell if there are 100 lines of code or millions in your app’s backend. Indeed, this is how most apps work: you don’t see the source code when you open Google Maps or Slack $-$ you just see the user interface.

In a business context, it becomes essential to only show the user what you want them to see, rather than reveal all your app’s secrets. You don’t want curious users discovering other users’ private data, for example, or sharing with the world how exactly your company’s nifty clustering algorithm works. In this case, our final level of abstraction is necessary for sharing your project.

Conclusions

This post set out to answer the question, “How do I share my coding project with someone?” The answer, it turns out, depends on how in the weeds you want your user to get!

The least abstract method is sending over a GitHub repo $-$ the raw code. This is ideal for collaboration, since your recipient can see exactly how your app works. But it can be hard for them to actually run your project, since they need to recreate all the libraries, languages, and perhaps even operating system you’re using.

The next level of abstraction is Docker, where you can create software “snapshots” that others can download. This removes the headaches of managing project dependencies, and most of the actual code is hidden from the user. They can still see, however, what services your app uses $-$ the exact flavor of database, whether your model uses Python or R, etc.

The final level is to host your code with a service like Heroku and send your recipient a URL. This completely hides any backend code from the user, which is ideal in a business context. This approach turns your recipient into a consumer of your product rather than a collaborator, since they have no idea what’s happening behind the scenes.

The right approach depends on how you want your recipient to interact with your project. But you also don’t have to choose only one of these ways to share code! In fact, I recommend sharing all of them with your user: the app in Heroku to immediately interact with it, the GitHub repo to see the underlying code, and a Dockerfile to run it locally.

Happy coding!

Best,

Matt

Footnotes

1. Level 2: Docker

Any time you talk about Docker, you probably need the obligatory disambiguation from virtual machines. While a Docker container is isolated from the rest of your computer (and other Docker containers unless you explicitly link them), containers do share host resources such as RAM and CPU, as well as use the same host kernel. If you don’t specify limits, a container can happily suck up CPU and slow down all containers around it. A virtual machine, on the other hand, has its own RAM and CPU and is truly isolated.

As a side note, when you run a Docker container with a Linux operating system on your Windows or Mac computer, Docker actually runs the container on a Linux virtual machine.

2. Level 2: Docker

One necessary leap from GitHub to Docker and Heroku is turning your project into an API, which lets other software (like a web browser) communicate with your code. You can do this with Flask in Python or Plumber in R.

3. Level 3: Heroku

A graphical interface is essential for apps whose audience includes non-programmers. But if your app is aimed at developers (e.g. the Google Maps API rather than normal Google Maps), the “front end” might just be a little welcome message in your command line. Either way, the backend code is still completely hidden from you.