Visualizing the danger of multiple t-test comparisons

#projects #r #statisticsWritten by Matt Sosna on May 13, 2018

It’s often tempting to make multiple t-test comparisons when running analyses with multiple groups. If you have three groups, this logic would look like “I’ll run a t-test to see if Group A is significantly different from Group B, then another to check if Group A is significantly different from Group C, then one more for whether Group B is different from Group C.” This logic, while seemingly intuitive, is seriously flawed. I’ll use an R function I wrote, false_pos, to help visualize why multiple t-tests can lead to highly inflated false positive rates.

Overview

For a given number of groups and observations per group, false_pos creates n_groups samples from the same (Gaussian) parent distribution, each with n_obs observations. Because these samples are drawn from the same population, any differences between them should not be statistically significant (i.e. p > 0.05).

The function then performs an ANOVA and all possible pairwise t-tests. The lowest pairwise t-test p-value and the ANOVA p-value are recorded. This is done n_iter times to form distributions of p-values for t-tests and ANOVAs, which are then plotted if figure = T. If pretty = T, the proportion of iterations with p-values below p.val is printed. (Default is p=0.05, but user can specify other values such as p=0.01). If pretty = F, a list is returned with summary statistics.

The functional arguments are listed below:

n_groups: the number of groups in the comparisonn_obs: the number of observations per groupn_iter: the number of iterations for creating the distribution of p-valuesp.val: the p-value to use when calculating the false positive rate (i.e. percent iterations below this value)verbose: as the function is running, should the progress be printed?figure: should a figure be printed?pretty: should the output be simple (pretty = T) or thorough (pretty = F)?

Note: false_pos.R also contains all code necessary to generate the figures in this post.

Background

Motivation

Many research questions involve comparing experimental groups to one another. The Dutch have an international reputation for their height, but is the average person from the Netherlands actually taller than people from, say, France or Sweden?

One way to find out is to measure every person in each of these three countries. (We’d have to measure quickly to account for birth and death rates!) With all 17.2 million, 66.9 million, and 9.9 million people carefully catalogued in our Excel file, we can take the mean of each group (representing the average height) and finally rest knowing whether the Dutch are, indeed, the tallest Europeans.

One issue: censusing this many people is an insane amount of work. Thanks to statistics, we can reach the same conclusion much faster with less effort. At its core, statistics is about making inferences about a population from a sample. We don’t need to measure every single Swede - we can measure a subset (our sample), and provided we’re sampling randomly and independently, our sample will quickly become an accurate representation of all of Sweden (our population).

One issue: censusing this many people is an insane amount of work. Thanks to statistics, we can reach the same conclusion much faster with less effort. At its core, statistics is about making inferences about a population from a sample. We don’t need to measure every single Swede - we can measure a subset (our sample), and provided we’re sampling randomly and independently, our sample will quickly become an accurate representation of all of Sweden (our population).

Alright, so we go out and sample 50 random people from each country. We plot our data and see that the distributions of heights look different, and the sample means indeed are a bit different… but are these differences meaningful? Unlike with our census of the entire population of each country, because we’re dealing with a subset, we have to take into account randomness in our sampling. Our samples are representations of the populations, but of course you’re going to distort the image a bit when you condense 66.9 million people into 50. How much of a difference in our samples do we need to see before we can declare the tallest Europeans?

t-tests and ANOVAs

A commonly-used method for comparing two groups is the t-test. t-tests are a simple, powerful tool (assuming the required assumptions are met in the data), and they’re a staple of introductory statistics courses. In short, a t-test quantifies the probability that the populations two samples are drawn from have the same mean. The sample means might differ, but a t-test translates that difference into an inference on the populations.

A t-test returns a p-value: the proportion of experiments where you would get your difference in sample means (or greater) if you ran your experiment thousands of times and if the two population means were identical. This accounts for the variability that sampling introduces into our analysis: yes, our sample means might be different, but of course you’ll get some differences between this random group of 50 French people versus the next random group of 50 French people. You’d expect a high p-value when you compare two samples from the same population: the samples are different but the t-test believes they’re coming from the same population. If we have a huge difference between samples, though, we would get a low p-value: the t-test believes it’s unlikely these samples came from have populations with identical means.

(As with any post on frequentist statistics and especially p-values, an obligatory word of caution.)

This all works well for comparing two groups, but when we compare more than two groups, we need to perform an analysis of variance. For our heights example, it can be tempting to run three t-tests: comparing the Dutch heights to French heights, Dutch heights to Swedish heights, and French heights to Swedish heights. This, however, is dangerous: multiple t-tests inflate the probability of (falsely) declaring that the two population means are different, when they actually aren’t. An ANOVA avoids this problem by restating the question as “are the means of all populations equal?”

Results

Visualizing false positive rates

We can use our custom function false_pos to easily visualize the problems of running multiple t-tests. Our function creates multiple groups that are sampled from the same population, so they should all be identical.[1] This should be reflected in having a t-test and ANOVA p-value above 0.05. Because there’s randomness in what exact numbers are drawn for each sample, let’s run this process 10,000 times to get a feel for the distribution of possible answers we could get. Let’s do this for three groups with ten observations each.

Above, we see the distribution of p-values for running multiple t-tests (gray) and the ANOVA (blue). For this run, false_pos tells us that running multiple t-tests gives you a false positive rate of 11.4%, whereas the ANOVA is 4.8%. We should expect a false positive rate of about 5%, which we get with ANOVA, but we have more than double the error rate with multiple t-tests.

Changing number of observations and groups

What if we change the number of observations or the number of groups? On one hand, increasing the number of comparisons should increase the t-test false positive rate. But what if we have more data per group? If we have a better picture of the parent population each sample comes from, will the t-test get better at recognizing that the samples are coming from the same place?

To answer these questions, we can run set ranges on n_obs and n_groups, then run false_pos on each combination of the number of groups and observations per group. This will let us know the relative contribution of making more comparisons versus having more data per group. When we do this, we get the heat maps below.

As we can see, t-tests are incredibly sensitive to the number of comparisons you run. As you move to the right of the figure (increasing the number of groups), the false positive rate steadily rises until you have around a 70% error rate when comparing 10 groups. Somewhat surprisingly, increasing the number of observations per group does almost nothing to lower the error rate. A strange exception exists for n_obs = 2, maybe corresponding to the fact that any differences between the groups are overriden by how low the sample size is, producing a low test statistic and hence high p-value.[2]

Meanwhile, the story is much simpler for ANOVAs: they are resilient. No matter the number of observations or groups, the false positive rate hovers around 0.05, exactly where we set our p-value threshold. This makes sense: wherever we set our threshold, we should expect this percentage of errors. (More on this in the Conclusions.) Below, we can see that the distribution of ANOVA p-values below 0.05 values lies neatly at 5%, as well as the mean false positive rate as a function of group size.

Conclusions

This post demonstrates how performing multiple t-tests between identical groups will produce high false positive rates, whereas ANOVAs successfully maintain accuracy. Note that all an ANOVA is doing is asking whether any of the groups being compared have parent populations with different means. Once we’ve run an ANOVA and determined that there are height differences between the Dutch, French, and Swedish, we would then need to use a follow-up method such as Tukey’s method or the Bonferroni’s correction.

When we set a threshold of p=0.05, we are accepting the fact that there is a 5% chance we reject our null hypothesis even if it is true. In other words, we would claim that the average Dutch person is taller than the average Swedish or French person, even if they aren’t. We can run our analysis again with a different p-value threshold and see that our false error rate matches the value we set for p.val. Below is the distribution of ANOVA false positive rates when we set p.val = 0.01. As we can see, the peak of the distribution is at the p-value threshold.

And to answer our original question, yes, the Dutch apparently are the world’s tallest people! Here is a summary from BBC on this article.

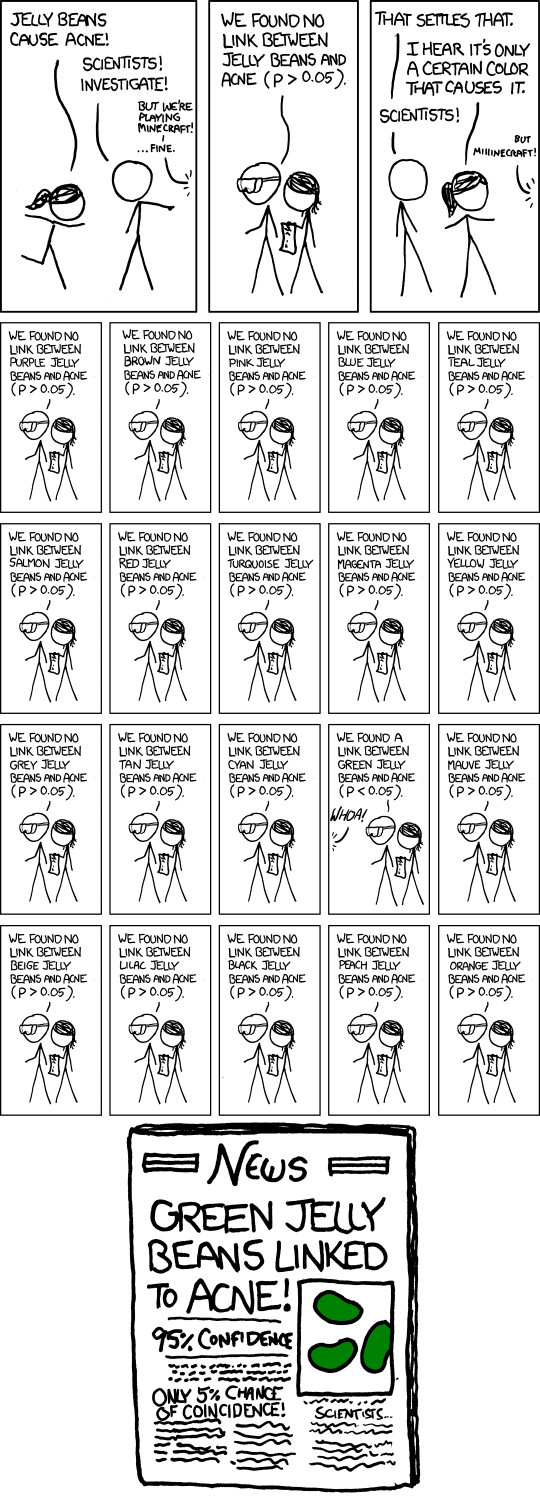

Finally, if you made it this far into the post, enjoy this xkcd comic by Randall Monroe, which perfectly describes the problem I tackled here. :-)

Footnotes

1. Visualizing false positive rates

I use rnorm to create each group. The parent population here is infinite. An alternate approach is to create a population that is then sampled from, e.g. the code below. However, this approach is slower, as the population needs to be stored in memory (and if you want to be thorough, a new population needs to be created with every iteration). Also, it becomes a little tedious to write the code to sample without replacement; it’s simpler to sample with replacement, but then as you increase n_obs, each group begins to represent a substantial percent of the parent population, and the groups begin to have many overlapping values. This then decreases the false error rate because it’s literally the same numbers in both groups.

| R |

1

2

3

4

population <- rnorm(1e6)

for(k in 1:n_groups){

groups[[k]] <- sample(population, n_obs)

}

2. Changing number of observations and groups

The t-test equations are helpful for wrapping your head around why increased sample size doesn’t help much: with more samples, we just end up comparing increasingly specific estimates of the population means. Even at 10 million samples each, for example, it’s still uncomfortably easy to get a significant p-value saying the parent populations are different.

| R |

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

for(i in 1:100){

set.seed(i)

sample1 <- rnorm(1e7)

sample2 <- rnorm(1e7)

result <- t.test(sample1, sample2)

cat('Iteration', i, '-', result$p.value, '\n')

if(result$p.value < 0.05){

break

}

}

# Iteration 1 - 0.1140783

# Iteration 2 - 0.2911598

# Iteration 3 - 0.6300628

# Iteration 4 - 0.06974418 # <- close O_O

# Iteration 5 - 0.9480819

# Iteration 6 - 0.5793899

# Iteration 7 - 0.6090801

# Iteration 8 - 0.2801767

# Iteration 9 - 0.9060832

# Iteration 10 - 0.3056238

# Iteration 11 - 0.4466754

# Iteration 12 - 0.02794961 # <- false positive