Writing the self-contained universe

#academiaWritten by Matt Sosna on November 23, 2013

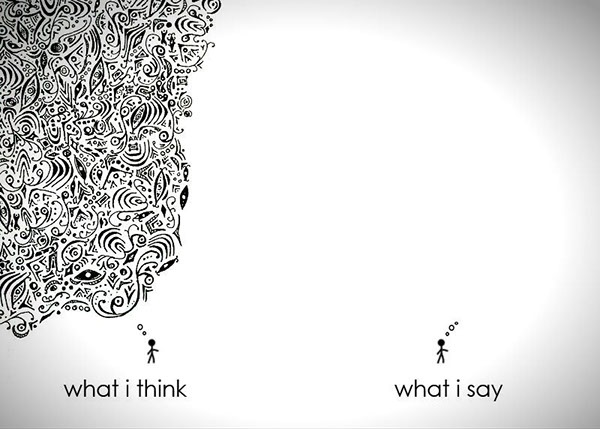

You are not sitting next to me right now as I type these thoughts. You’re most likely not in New Jersey, and you might not even be in the U.S. The fact that it’s even possible for you to be reading these words right now highlights the power of communicating ideas through writing. Effective communication is the difference between you growing bored and leaving halfway through this blog post to explore other parts of the internet, and you reaching the end (before moving on to explore the rest of the internet!).

In essence, writing is just a means of getting info from Point A to Point B. No matter how many amazing and intelligent ideas you may have in your head, they will have to stay there if you don’t know how to communicate them. Here are a few tips on bridging the gap between you and your reader’s mind when it comes to e-mailing a professor or potential collaborator, writing a grant, or explaining your ideas in general.

1. Who is your reader? Why should they care about your message?

Example: e-mail

As often as possible, put yourself in the head of the person reading what you wrote. Let’s say you’re e-mailing a professor to potentially do a PhD with them. They’ll want to know:

- Who is this person? Is he/she currently an undergraduate? If not, what has she done since then?

- What are his research interests? Of my work, what interests him?

- What are her research qualifications? Has she done research before, or is she just applying to grad school because she hasn’t considered other options?

- Has this applicant actually read up about my lab and thinks he’s a good fit, or is he just sending a template e-mail to every researcher he can find?

The more of these you can answer, the more willing the professor will be to respond. Remember that professors are incredibly busy people. While they undoubtedly enjoy exchanging ideas with new people, they often have overflowing schedules and email inboxes, and their time is very limited. The easier you can make an e-mail exchange for them, the less time they have to spend answering these questions themselves. You want a researcher to be nodding her head as she reads the e-mail, her questions being answered as she reads so that by the end, the work has been done for her and she can now focus on writing her response.

2. Does your writing actually address the purpose of the message?

Example: grant writing, lab reports

Say you’re working on an NSF-GRFP grant (the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship). You have phenomenal research ideas that would explain a genetic basis for sociability in humans, and you have told a heartwarming story on how you discovered and decided to pursue science. A few months later, you’re surprised to find your revolutionary ideas were not funded by NSF. What happened?

Say you’re working on an NSF-GRFP grant (the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship). You have phenomenal research ideas that would explain a genetic basis for sociability in humans, and you have told a heartwarming story on how you discovered and decided to pursue science. A few months later, you’re surprised to find your revolutionary ideas were not funded by NSF. What happened?

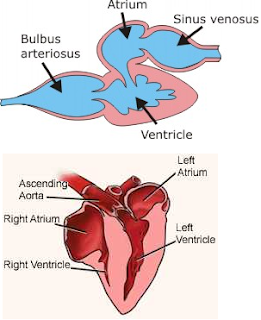

It’s likely that you didn’t answer every part of the application to the degree NSF was looking for. Consider an introductory biology lab in which the students dissect fish and chicken hearts (diagrams on the right). In their report, they are asked to compare the two hearts and explain how these hearts differ in the ability to support different levels of metabolic demand. Unless they provide 1) comparisons between the two hearts and 2) explain how those differences affect ability to support varying metabolisms, they will not get full credit, no matter how detailed either component of their answer is. Think of it as:

10 points total:

- 5 - provide 3 differences between the 2 hearts

- 5 - explain each difference in terms of metabolic potential

You can slam dunk those first 5 points, but if you don’t address the second section, it’s likely you won’t even get a passing grade. Similarly, regardless of how incredible your GRFP research proposal is, if you don’t explain how your work has any relevance outside your field, applications with even the very best research ideas will get turned down. Again, think from the GRFP officer’s viewpoint: every applicant has good ideas, but NSF wants research fellows who will not only advance science but also help spread its ideas beyond the scientific sphere. Even if you would do outreach if you had the opportunity, if you don’t write about it, the GRFP officer can’t assume you would.

3. If your writing was an isolated universe, would that universe make sense?

Example: course exam

This is one I repeatedly tell my introductory biology students for their lab reports and exams. Imagine your parents somehow stumbled across your biology midterm essays (of all the things they could have discovered in your room) and were reading them. Would they be able to understand what you wrote? In this situation, you have people who maybe haven’t taken a biology class in a few decades, if ever. Do they get lost in your jargon, or is your answer self-contained enough for anyone to be able to pick it up and learn something from it? One of the biggest roadblocks to good communication is losing your audience partway because you assume they understand something they actually don’t. Being able to grab a listener from any background and pull them to a new level of understanding is challenging, but it’s critical for teaching.

4. If a reader skimmed your writing, would they still get your message?

Example: lab report, scientific articles

How long do you think your reader will spend on your writing? Many science majors in college are under the misconception that their TAs and professors meander through their lab reports, slowly chewing on every word. Many newcomers believe that a longer lab report is a better one - more words means more opportunities to stumble onto a sentence that earns points, right? The idea, which seems reasonable at first, is that the more information you put down, the larger the net you are casting, which has a better chance of catching the answer your TA is looking for.

Unfortunately, it’s not quite like that. Aside from giving yourself more opportunities to write something incorrect and actually lose points, in the scientific world you will almost never be in the situation where you’ve written everything you need and should keep writing more.

Again, think about writing as a communication of ideas. In science, short and sweet (i.e. efficient) is always preferable to long and winding. Scientific articles have abstracts so readers can get the gist of the article without needing the motivation, background, and time to read the entire thing (remember how busy many researchers are!). Articles in the journal Science actually have one-sentence summaries for researchers in related fields who just want the core finding. Brevity is a much better skill to have than the ability to list everything you know about a topic.

Consider the reader, consider your miniature universe. And if all else fails, just call your reader on Skype.

-Matt

Photo credits:

- Thinking: Basic College English blog

- Chicken heart: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Chickscope

- Fish heart: Stanford University Environmental Science Investigation