Ph.D. reflections 3rd year

#academia

Written by Matt Sosna on August 12, 2016

Year three. If an American PhD takes 5-6 years, then this is when you pass the halfway point. You’re now in the thick of the weeds. The big picture science that originally got you into this PhD gets harder to remember. The questions you set off to answer years ago really need to stand up to the second guesses that come from when you start dedicating hundreds of hours to answering them. It gets hard not to hear those quiet voices asking if there’s a better way to do things: is academia the path of most happiness for me, what’s consulting or industry like, am I actually doing interesting work? And of course, the eternal question of investing in automation versus doing the mind-numbing manual work! (See xkcd for the right ratio of investment to payoff!)

Year three. If an American PhD takes 5-6 years, then this is when you pass the halfway point. You’re now in the thick of the weeds. The big picture science that originally got you into this PhD gets harder to remember. The questions you set off to answer years ago really need to stand up to the second guesses that come from when you start dedicating hundreds of hours to answering them. It gets hard not to hear those quiet voices asking if there’s a better way to do things: is academia the path of most happiness for me, what’s consulting or industry like, am I actually doing interesting work? And of course, the eternal question of investing in automation versus doing the mind-numbing manual work! (See xkcd for the right ratio of investment to payoff!)

For me, this year was when I changed the course of how things were going and got myself on track. I finally realized that - at least for me - the only one in charge of where this ship was going was me, and I needed to stop waiting for… everything. For approval for hard work, for external confirmation that what I was doing was correct, for someone to specifically tell me what the next step should be.

Background

My experience is likely different from many other biology doctorates - especially those working with junior faculty or at institutions with less guaranteed funding - so it’s worth explaining here briefly. Early in my PhD, my advisor left Princeton to start a new department at the University of Konstanz, in Germany. The first few months, around the middle of my second year, were little different from before: I had plenty of opportunity to get advice from him on experiments and the lab still had about 15 grad students and post docs. (Yes, it was really that big!) But as time went on, my advisor’s attention grew increasingly split between the new Germany crew - eight PhDs, two post docs, and two PIs at the start - the Princeton group, and the never-ending administrative work required for starting not just a lab but a whole department. Meanwhile, the lab here steadily shrank as older students graduated and postdocs moved on to professorships elsewhere.

I found myself in a bit of an odd place: there wasn’t really anyone watching over me. I would periodically meet with other Princeton animal behavior faculty who were incredibly generous and patient with me, but ultimately I didn’t have anyone to turn to who really understood how to navigate the “little things” with collective behavior experiments. How do you summarize 40 time series that are spatially and temporally correlated? Do fish prefer white noise or silence in the room during experiments? I was deeply grateful for the faculty’s help, but I was on my own for a lot of these decisions.

Essentially, I had laboratory funding but little guidance. I could theoretically do whatever I wanted… but while that meant glorious freedom, it also meant there was nothing stopping from me trying to push through a concrete wall. What if I made a mistake? What if I wasted a lot of lab money, or I dedicated months to a project that wasn’t going to work?

Through much of 2015, I found this apprehension immobilizing. I was so afraid of making a mistake that I wouldn’t try an experiment until I had thought through all the details dozens of times - even though I knew in the back of my mind that the details would undoubtedly change once the experiment started, anyway. It took much thinking to realize that mistakes were inherent to the scientific process, and I really just had to get my hands dirty. That meant ordering a brand of UV lights that I ended up not using, or dedicating a few days to trying a new experimental method I sometimes didn’t use in the end. Those false steps were necessary in finding the right path to take.

Year summary

Thesis

Following the theme of the second-year PhD reflections, animal research is challenging. Acquiring data can be very tricky. For the first half of the year, I kept myself busy with learning as much R and network science as I could, two skills I would need to have sharp for the types of analyses I eventually would need to do. But by January, it was time to focus on collecting the data for those analyses. I decided to try a new approach to the fish experiments and I enlisted the help of two fantastic Couzin Lab members: Geoffrey Mazué and Joe Bak-Coleman. We actually flew Geoffrey in from Germany for this, and I’m really glad we did: when our order of 300 golden shiners arrived, “300 fish” turned out to be 1200. Thanks to some quick thinking and coordination with animal resources administration, we were able to find a home for all individuals.

The next two weeks passed by at a crawl. We store fish in tanks on a flow-through system, meaning all water gets cycled through the same biological filter. Various species of bacteria in the filter convert ammonia waste to nitrite, then nitrite to nitrate, before the nitrates are gradually cycled out as fresh water enters the system. The relative balance of these bacteria species is crucial, because if there is a spike in resources and one species outcompetes the others, you now have a block in waste treatment for the whole rack. Adding dozens more fish per rack than we expected meant we had a spike in ammonia coming, and we had to keep a close eye on the water parameters so we’d know when to make key adjustments to the water to avoid jostling the delicate bacterial balance too much. The flow-through system also meant we had to keep close tabs on hundreds of fish to spot anyone who looked sick so we could isolate them for treatment and avoid contaminating others. We spent hours each day observing the fish, testing water quality, and adjusting as necessary.

Luckily, our hard work and partnership with animal resources administration paid off. At the end of two weeks, I had over a thousand fish ready for use in experiments. Over the next weeks, I began grinding away at data collection. Thanks to Joe and the lessons we learned in January, I was able to continue data collection through May with two more orders of fish.

The arena where I conduct my experiments. The UV lights allow for individual identification if the fish are marked with fluorescent tags. A camera is positioned above the tank; the tank is white to allow for automated tracking of individuals with software. Part of the hesitation I had to learn to overcome was that the experimental room came with only the tank and curtains. I had to figure out the lighting (and its support) and the camera (and its mounting). Trial and error is your friend!

Meanwhile, I also worked to develop a new study system at Princeton. I’m fascinated by antipredator behavior, yet treating predators as static sources of abstract “risk” misses out on half of the picture in a predator-prey interaction. Following months of working closely with IACUC (the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee), laboratory animal resources, and colleagues with experience in the system, I gained approval to conduct some experiments I’m really excited about. Everything is still very preliminary, so check back in the PhD: 4th-Year reflections post! [You can find that here.]

Outside the thesis

This year, I realized I needed a balance to the thesis. A PhD operates on such a long time scale that it’s easy to get discouraged at the slow pace, or to feel like there’s nothing in the world besides the stress of your thesis. The question of relevance is also something so many graduate students grapple with: “is my work actually improving the world at all?”

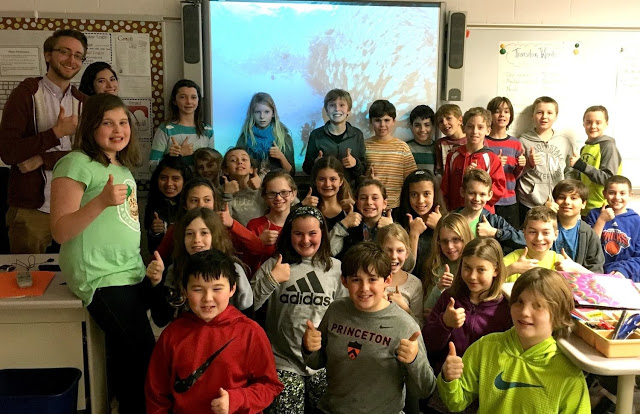

For me, increasing public engagement, understanding, and access to science was the “big picture” goal I wanted more of in my life. After receiving a mass e-mail advertisement from post-baccalaureate astrophysics student Aida Behmard, I helped start the Princeton chapter of Open Labs, a science outreach group that delivers TED-like talks to K-12 audiences. Throughout 2016, Aida and I coordinated and gave talks at Hopewell Elementary School and helped judge their science fair, organized two on-campus lecture series for local high school students, and spoke with high school students in the Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity in Trenton.

Happy faces after talking science with 5th graders at Hopewell Elementary School. Open Labs is grateful to the teachers who let us speak with their students! They were incredibly insightful and curious, and it was a lot of fun hearing their thoughts.

On the writing end, a random conversation with Julio Herrera Estrada led me to helping found the interdisciplinary sustainable development blog Highwire Earth, as well. Julio and I wanted to do something about how little cross-talk there existed between research departments at Princeton. Many of us are unknowingly researching similar topics, for example, and there are missed opportunities for sharing methods and ideas. For unprecedented global challenges such as addressing climate change, we can’t afford to work in isolation. Highwire Earth aims to be a platform where students from varied disciplines write about addressing global challenges from different viewpoints.

Finally, I want to give a shout out to MAVRIC, a great feminist resource on campus. Every other week, I attended lunches where we discussed gender equity, body image issues in the media, and pressures men face to hide their emotions. It’s a great community and really helped organize my thoughts on how to be a better ally.

What I’ve learned from 3rd year

Learn to be self-sufficient

More broadly, learn how to learn what you need. What’s stopping you from doing an experiment or a particular analysis? Research is all about not knowing the exact path. It took me a while to learn how to approach problems like this and break them down, how to keep moving forward by trying things.

Pilot everything. No exceptions!

You will save so much time and stress if you test-run everything. Everything. Do not run an overnight analysis unless you’re sure all parameters are best-fit to the videos or data. Do not commit to a week of experiments unless every detail of the methods is confirmed to work. You will have to redo these things if you get them wrong, so invest the time at the start to get it right so you save time later. Piloting can feel like wasting time when you just want to get on with the actual experiment, but it’s well worth the investment.

You are not stuck in academia if you develop transferable skills. Academia is a choice

I know an unfortunate number of PhD students who feel stuck in academia because they lack the necessary skills to transfer into another job such as consulting, data science, or analytics. It took much prodding from my partner - a non-scientist outside academia - for me to realize I could choose whether to be in academia or not. Get the certifications you need if you’re thinking about working for the national park service or at a research station. Create a solid portfolio of digital artwork if you’re interested in web design.

If you develop analytical skills such as R, Python, or SQL, you not only improve your analytical ability for your thesis: you also become a highly attractive candidate for non-academic, well-paying jobs. Employers will value the independence and critical thinking you gained from your PhD as well as your analytical skills. The freedom to leave academia if you find it’s not worth it - or, equally importantly, to have an edge in data analysis if you continue in academia - really helps with the stress of the PhD. For me, I’m excited to continue down the academic route. I also know, though, that I’m developing skills that can keep other doors open down the line.

Cheers,

-Matt