Transitioning to data science from academia

#academia #careers #data-scienceWritten by Matt Sosna on February 10, 2021

“I could always do data science if academia doesn’t work out.” It’s a recurring thought many graduate students and postdocs experience, especially if their work involves hearty servings of programming and statistics, the core elements of data science. Data science can be a rewarding alternative to academia, and academics do have many qualities that make them attractive candidates for data science roles. However, there are also often large holes in academics’ skill sets that can deter them from being hired straight off the bat.

This post will outline the skills needed to make the leap from the ivory tower to industry. We’ll go light on the technical details or business acumen; for a deep dive on those skills, check out my five-part how to enter data science series. Especially if you’re just starting to consider data science as a career, I highly recommend thinking about where your ideal role falls on the analytics-engineering spectrum, which will help you identify which skills to prioritize learning.

Table of contents

What are we working with?

Where academics excel

Successful research is incredibly challenging. Making it through a Ph.D. (and beyond) requires significant mental and emotional growth. If you’re surviving the challenges of independent research, then you undoubtedly have:

- The ability to distill interesting questions from large amounts of information

- The analytical chops to answer those questions

- Extreme attention to detail

- Strong planning and organization

- Serious mental fortitude to push through (and learn from) failure

Many of the skills you gain in graduate school align nicely with what makes for a strong data scientist. In both cases, you need to think critically about what questions to ask, how to get data, and how to extract meaningful insights from that data. Both professions need to communicate and coordinate with stakeholders of varying backgrounds. Finally, both are expected to continually learn, and to innovate solutions when none already exist.

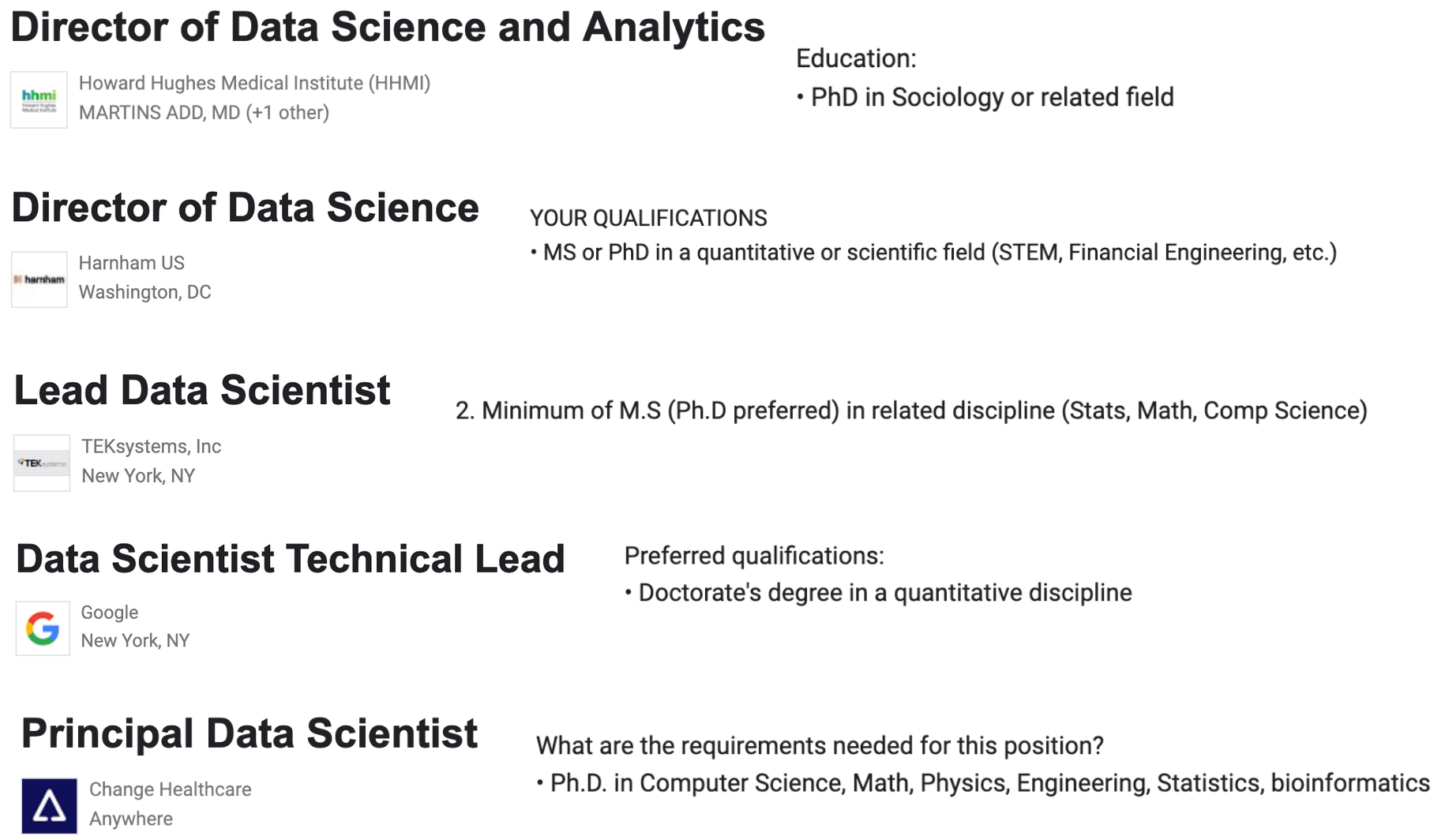

It’s hard to overstate how valuable these skills are. Many senior- or director-level data science positions require a Ph.D. because of the rigor academic research brings to identifying ways to solve tough problems. Below are a few senior roles I found with five minutes of searching on Google, along with their expected education level. Maybe these requirements will loosen over the years as the field matures, but for now, having a Ph.D. is a major asset for your career progression as a data scientist.

Where academics struggle

The attractive jobs above, however, assume that you unlearn much of the mentality from grad school. While the skills you gain in academia are incredibly valuable for data science, the priorities are often actually a detriment. Here’s where I think academics often struggle when switching to roles outside academia.

-

The speed-accuracy tradeoff. Academia prioritizes precision to the tenth decimal place. The point of research, after all, is to uncover the truth no matter how long it takes. But 100% accuracy just isn’t realistic for many companies, given their limited resources. “Good enough” can be a tough concept to swallow, and your workflow will likely need to shift to maximizing accuracy as fast as possible under limited time.

-

Implementing the results of an analysis. Unless you’re in a data science role that’s effectively still academia (e.g. Mathematica, Brookings), it’s not enough to just generate knowledge. You need to then convince stakeholders to adopt your results, which calls on an entirely separate set of business skills. If you work for a tech company, incorporating your results will also call for another entirely separate set of software engineering skills. These skills gaps can sneak up on you, and they’re painfully visible $-$ the difference between a mediocre and stellar predictive model requires a trained eye, but anyone can see that your model isn’t available to users weeks after you said it’d be.

-

Focusing on team above self. When you leave academia, you transition from maximizing your personal output, to maximizing your team’s output. Yes, in academia you invest significant effort into the success of your collaborators and students. But your name is still front and center on any paper, poster, or seminar your coauthors produce. Outside of academia, you become a lot more anonymous. It can feel disheartening to have your name detached from your work, your contributions invisible to anyone outside your company. (And likely invisible to many within, too!) Similarly, it can be challenging to transition from the fierce independence of academic work to working on literally the same codebase with coworkers and needing to abide by programming best practices and product management, not just what worked for you personally in grad school.

-

Working on something you don’t want to do. The unbridled freedom in academia, especially for U.S. programs, means you’re free to pursue the questions you most find interesting. If you can get funding for your idea, there’s no one stopping you from charting your own intellectual path. In industry, meanwhile, your hands are tied firmly to the questions your organization has decided are worth pursuing. You have some say in this, of course, but if your boss puts their foot down on another linear regression, that’s what you’re doing.

These issues take time to overcome. Maybe you can easily turn off the “100% accuracy” mentality, but it’ll take more than a few afternoons to pick up software engineering skills like Git, SQL, and working with APIs. And while you’re applying for jobs, it can be disorienting to have the impressive credential of a Ph.D. while simultaneously be outcompeted by fresh computer science or boot camp graduates. This next section will focus on how to smooth the transition into a new role.

Tips for the transition

The mentality

When you enter the job market, it’s useful to think of yourself as selling your labor to an employer. What do you have to sell? During your Ph.D., you likely developed expert-level skills in performing certain kinds of analyses on certain kinds of data. Maybe you’re really good at finding patterns in astronomical radio waves, for example. But who’s willing to pay for that skill? And even if NASA is hiring, how do you feel about continuing the same work you just did for half a decade?

If you love your research, want to continue it, and there are non-academic employers willing to pay for it, then you’re in the great position of already being fully qualified for your first role out of academia. Congrats! But for the rest of us, there’s a lot of catching up to do to become competitive applicants. Regardless of where you’re aiming on the analytics-engineering spectrum, there’s a shift in how you view yourself as a coder that’s required for you to succeed in industry:

What you might be thinking:

“I can code anything I want.”

What industry wants:

“I can code anything anyone asks me.”

When you have the flexibility to choose the research questions you pursue, as well as how you go about answering those questions, it’s easy to gravitate towards questions and methods you’re comfortable with. In a way, a Ph.D. is all about getting really good at a narrow set of skills: you choose a very precise question to answer, and you work until you know more about this sliver of knowledge than anyone else in the world.

You don’t have the luxury of a narrow skill set when you’re a data scientist, especially if you’re at a smaller company. There’s a term called “full-stack” in software engineering $-$ it refers to programmers who can code professionally in both the front-end and back-end environments, which require entirely different languages and perspectives. Data science is like being a full-stack analyst: you need to be comfortable rotating between extracting insights from data and then building the infrastructure to communicate those insights (such as dashboards and automated scripts).

During my Ph.D., I found it incredibly easy to stay in the areas of R and statistics that I already knew well. I didn’t want to get out of my comfort zone, because it would require me to face the scary concept that I didn’t actually have that strong a grasp on stats and coding. I felt like since I was using R and stats in my thesis, others expected me to be an expert. Taking formal stats or R classes would therefore violate these expectations and expose me as not being an expert. Ironically, all this fear did is stop me from actually developing a solid, well-rounded understanding of R and stats. I also doubt anyone cared about how much I knew anyway.

Don’t make the same mistake I did $-$ embrace not knowing everything, and get started on filling in the knowledge gaps. You need a wide range of skills to be an effective data scientist, and those skills need to be maintained and polished. I recommend checking out the datasets and challenges on Kaggle, HackerRank, and Reddit. Make sure to work through some projects rather than just taking notes on online classes $-$ this will give you a much stronger understanding of the topic, and you’ll have something to show potential employers afterwards.

The targets

Unless you truly don’t care where you work when you leave academia, you’re probably trying to perform two transitions at once: 1) entering data science, and 2) entering a new field. My recommendation is to first transition to data science, build up some skills in a professional environment where you can learn from your peers, then transition to your preferred field. Even with a Ph.D., it can be hard enough to land your first job, so cast a wide net! Ideally, try to land at a company with established teams of data scientists, analysts, and engineers, somewhere you can soak up knowledge from everyone around you. This is especially important if the field you want to eventually work in doesn’t necessarily have dozens of data scientists and engineers you can learn from when you arrive.

Once you’ve put in your time at your first role and feel ready to make your second transition, start really thinking about what you’re looking for. For me, I wanted to contribute to fighting climate change in some way, but I had no experience in this area besides having a bio degree. Once I started searching for jobs, I realized I’d need to be much more specific. Did I want to work at a nonprofit or think tank? What about government $-$ and if so, was that municipal, state, or federal? Did I want to join a sustainability company, a sustainability department within a larger company, or a sustainability consulting firm? And even within sustainability, did this mean electric vehicles, renewable energy, batteries, aviation, heavy industry, building retrofits, waste reduction, or something else?

You don’t need an exact answer to these questions for your own search, but thinking carefully will help narrow down what you’re looking for. For me, I realized I wanted to hone in on tech for sustainability, so I stopped looking at the think tank, nonprofit, and government positions.

The applications

Cut your publications from your resume.

Yes, you need to cut them. It’s one of the most painful parts of the transition. The central currency in academia has very little value outside the ivory tower, unless you’re applying to join a team of Ph.D’s at some think tank. Otherwise, add a link to your Google Scholar profile, hit save, then go for a walk and have some ice cream.

While cutting the publications is painful, with a little effort you can fill out a projects section that employers will find much more interesting. For better or worse, writing code is something you can do anytime, anywhere… including outside your normal job. It’s controversial and problematic to expect coding side projects in a resume, but I think it’s well worth the extra effort when you’re trying to break into the field.[1] If you can afford the time to create a GitHub repo with some examples of simple projects, you can greatly strengthen your resume by having concrete examples of what your code looks like and how you solve problems. Think of a hiring manager as someone deciding whether to hire an artist $-$ it’d be good to know what the artist’s work looks like, no?

Finally, when you’re submitting applications, always include a tailored cover letter explaining why you want to work at the company, why you’d be a good fit, and your biggest contributions in earlier roles. There’s not much I can add that hasn’t already been extensively covered elsewhere; check out this cover letter example and these resume tips. Don’t bother with a fancy resume builder $-$ Google Doc’s free one-page templates are great.

Conclusions

There can be a lot of conflicting feelings when you’re considering leaving academia. I loved the idealism of it $-$ bringing together passionate, sharp people to work on problems no one in the world knows the answer to. Teaching students every week was a privilege. And it’s hard to beat being paid to travel to conferences and exciting field sites $-$ I’ve been lucky enough to visit Africa twice, and I almost went to Antarctica.

But a successful career in academia requires a lot of dedication: it’s like being an athlete. You need to be truly dedicated to your topic, willing to chew on the same tough problems for years, constantly justify your work to funders, and read every bit of relevant literature that comes your way. Even with a consistent publishing record, unless you’re at the top of your field, you need to be willing to move every few years to a location you can’t really predict in advance. Despite being a field consisting of people who spend all day thinking, there is plenty of institutional inertia around problems like how manuscripts are vetted, how scientific contributions are evaluated for tenure, and how to address systemic inequities. Academia is an amazing career for some people, but for me, I slowly realized data science was what I was looking for.

Even knowing all this, the transition is hard. Changing your identity can leave you vulnerable, and it’s hard not to feel embarrassed or frustrated at how many steps backward you have to take when you start a new career. There was a day a few months into applying to jobs where I got rejected from two the same day, both consisting of teams of Ph.Ds. To be fair, one team was Ph.D. economists and the other was Ph.D. computer scientists (my degree was biology), but it was hard to be rejected even among my “peers.” I’d spent all that time in grad school becoming a well-rounded experimentalist and theorist, someone who could set up a laboratory fish study system, run experiments, extract the data, analyze it, and communicate it, but the feedback I was getting was that none of that mattered. I either didn’t know enough advanced stats, or I didn’t know enough engineering, or I wasn’t given a reason at all.

As demoralizing as it can be, just keep applying, and just keep learning. I wrote the “how to enter data science” series in part because I remember how hard I found it to identify what skills I actually needed when I was entering the field. But you also don’t have to go through the transition alone. There are several coding boot camps aimed specifically at Ph.Ds looking to enter industry, such as the Insight Fellowship and Data Incubator. While you undoubtedly have the discipline to teach yourself the skills you need, it can be far more efficient to have professionals help you.

Don’t hesitate to reach out if you’d like to chat. Good luck!

Best,

Matt

Footnotes

1. The applications

The key word here is “expect.” I don’t think anyone should expect an applicant to have coding side projects in their resume. The tangible examples definitely help, especially when the applicant is first entering data science. But a career is just one slice of someone’s life, and that needs to be respected.