How to enter data science 5. The people

#careers

#data-science

Written by Matt Sosna on January 21, 2021

So far, we’ve covered the technical side to data science: statistics, analytics, and software engineering. But no matter how talented you are at crunching numbers and writing code, your effectiveness as a data scientist is limited if you chase questions that don’t actually help your company, or you can’t get anyone to incorporate the results of your analyses. Similarly, how do you stay motivated and relevant in a field that’s constantly evolving?

In this post, we’ll outline the business and personal skills needed to translate your technical skills into impact. We’ll first focus on business skills before turning to personal skills.

And of course, some disclaimers: I’ve spent my data science career so far at companies with fewer than 100 employees. This post would likely look different if I’d spent the last ten years as one of Oracle’s 135,000 employees! I’ve also never worked in the government or nonprofit sectors. Regardless, I’ve done my best to minimize this bias and write a post applicable to data scientists at organizations of any size and type.

How to enter data science:

- The target

- The statistics

- The programming

- The engineering

- The people

Making sense of business sense

Data science is full of tempting rabbit holes. Our code works fine, but what if we added a way to automate tuning model hyperparameters? Maybe the stakeholders would be more engaged if we built a better way to visualize the high-dimensional vector space of our NLP model. Nobody asked for it, but what if we built a sleek dashboard for our data quality outputs so you could click buttons instead of needing to write SQL?

The confusing thing is that while there usually is some business value at the end of the rabbit hole, it’s often not worth pursuing. Sure, a model that is more accurate or easy to understand will probably help your company in some way. But is this the highest-leverage use of your time? Can you understand your coworkers’ needs and communicate how this project will empower them? And is this project addressing an unmet need in your company’s market, or is it a “nice to have”? We’ll explore these ideas in the rest of this section.

Optimizing resource allocation

Here’s an example of a dilemma you may face as a data scientist. Your company asks you to forecast sales in New York next quarter. After a month, you present what you have so far $-$ an ARIMA model with an RMSE of about 5,000. While this is pretty good, you’ve identified two additional exogenous variables that you believe can decrease error to 2,000! You end your presentation with a plan of attack for exploring and incorporating these variables.

To your surprise, your boss says no. The model’s accuracy is acceptable, they say, and it’s not worth the time (and risk) of exploring further. You’re given a week to productize your model, after which you’ll start on a new project. You’re confused and are sure your boss is making a mistake. How is it not worth just two weeks to potentially halve the model error? There’s a real cost your company will pay by using less accurate projections!

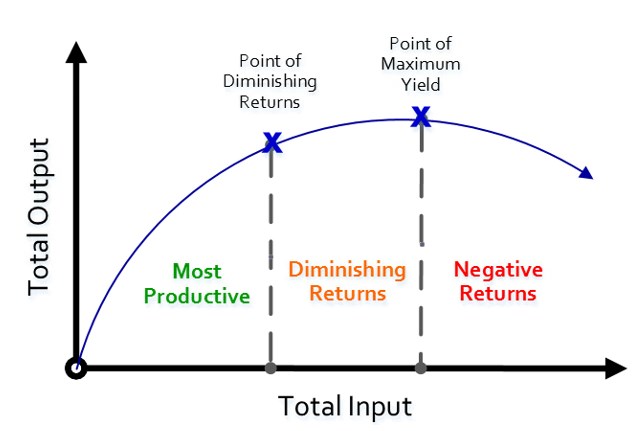

To understand your company’s perspective, consider its ever-present need to optimally allocate resources. Yes, a less accurate model means your company is using worse projections, which may result in less accurate decisions. However, the cost of this inaccuracy is likely lower than the opportunity cost of you not working on a different business need.

In the context of the company’s needs, perhaps the effort invested in the model so far represents the point of maximum yield in the graph below, or even just the point of diminishing returns. In other words, your company is willing to pay the cost of a worse model if it means avoiding a larger cost, such as customer churn due to errors in their orders. To your company, it’d be more valuable to stop your work on forecasting and instead turn you to data quality.

Source: The Peak Performance Center

It’s easy to get frustrated by being cut short on a project, especially if you’ve sunk time into it or have finally built up steam. It’s important, though, to separate your feelings about a project from your judgment on whether it’s worth pursuing. Focusing on how you can best benefit your company, rather than just pursuing questions you alone find interesting, will make you a far more effective employee.[1] Your company’s key performance indicators and roadmap will help you understand what leadership at your company finds valuable.

The next sections will cover how to best help your company through empowering coworkers and understanding the market. A solid understanding here will enable more productive conversations with your boss, product manager, or other internal departments. It will also help build trust in data science initiatives you may bring to the table, as you will be able to better communicate how they will help the company.

Empowering coworkers

Let’s get something out of the way upfront: the best way to empower your coworkers is to ask them what they need. You’ll save a lot of time and effort by getting your coworker needs from the source, rather than guessing at what they want. Your sleek and informative dashboard doesn’t matter if it’s answering a question your coworkers aren’t actually asking!

Your non-technical coworkers usually don’t need fancy machine learning to be more productive. For someone who doesn’t code for a living, their major pain points are more likely to be:

- The amount of time they spend clicking around to gather or move data

- A lack of visibility on issues they’re responsible for (e.g. data quality)

Luckily, these are areas that can be straightforward to automate and can dramatically help your coworkers. You can get a ton of mileage, for example, from creating Python scripts that run nightly, pulling data from various sources and outputting a CSV that’s automatically pulled into Google Sheets or sent as an email.[2] (If every request you hear is about accessing data, though, this is a bigger issue, and one for the software engineering or data engineering teams.)

But let’s say that the need you’re fulfilling is more technical, such as a model for detecting anomalies or forecasting sales. For these more complicated offerings, it is essential that your product is highly reliable and easy to understand, especially if your user is in a customer-facing role. Put yourself in your coworkers’ shoes: imagine the nightmare of using some flaky Flask app for a meeting with an impatient customer, the app crashing while the customer is staring at you, and then not being able to figure out how to restart the app. Your impatient customer is now one who didn’t get the services they paid for, and now you need to awkwardly and apologetically pick up the slack next time to convince them to remain a customer.

Avoiding headaches like these, as well as the annoyance of being less productive while learning to use a new tool, can make coworkers hesitant to use your product. This is the case even if they in theory agree that your product should make them more productive! The key here is to build trust in your product. Communicate with your stakeholders as often as you can while you’re planning and building the product. Once the product is “done,” expect to spend a good deal of time writing documentation, training coworkers, answering their questions, and incorporating their feedback. If you can, watch how your coworkers actually use your product live $-$ this is the ultimate test of whether you’re accomplishing your goal of enabling them. And always remind them that the point of this product is to help them; if it needs to change to actually be useful, that’s just part of the workflow.

Understanding the market

Your company doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Beyond the walls of your office are customers, competitors, investors, and regulators, each affecting your business in a different way. What do they care about, how is that changing over time, and what does it mean for you? What is the core offering of your company, and what need in the market is it fulfilling?

These are tough questions that your sales, marketing, and leadership teams generally spend all day chewing on, so don’t feel bad about not being an expert. But to vastly improve the value you can bring to your company, seek to understand this context your company is in. The right answer to the question “Is it worth the effort to build a spending forecaster for our customers?”, for example, depends on a lot of factors outside of your company. Have the customers been asking for this when interacting with your company? Do competitors offer this service (and if they do, can you do it cheaper)? Does your sales team overhear industry leaders grumbling about struggling to plan their finances? The answers to these questions differ between industries and over time, so you need to keep an eye on them to ensure you’re delivering a product people will actually use.

But what about innovation? Innovation involves creating new solutions to existing problems, or redefining existing problems into ones we can solve.[3] We’ve seen this happen in dozens of industries over the last decade with the explosion of machine learning. Can’t we just create a data science model or application that is objectively useful, one that drives market change instead of just following it?

Unfortunately, it doesn’t really work that way. The issue is that innovation is a method for answering questions, while it’s the questions themselves that actually contain the business value. Innovation by itself doesn’t contain business context $-$ you can easily “innovate” solutions to problems that nobody has! Machine learning transformed industries from agriculture to zoology because it answered questions people cared about. There was an underlying need that machine learning was able to address, but it didn’t create that need. For your work to be impactful, you need to be able to identify these high-value needs.[4]

The self parameter

The previous section covered the business aspects of data science: understanding your company and coworkers’ perspectives, as well as the broader market context. We’ll now shift inward and focus on the mentality and habits needed for you to maximize your potential and consistently deliver great work.

CI: Continuous Improvement

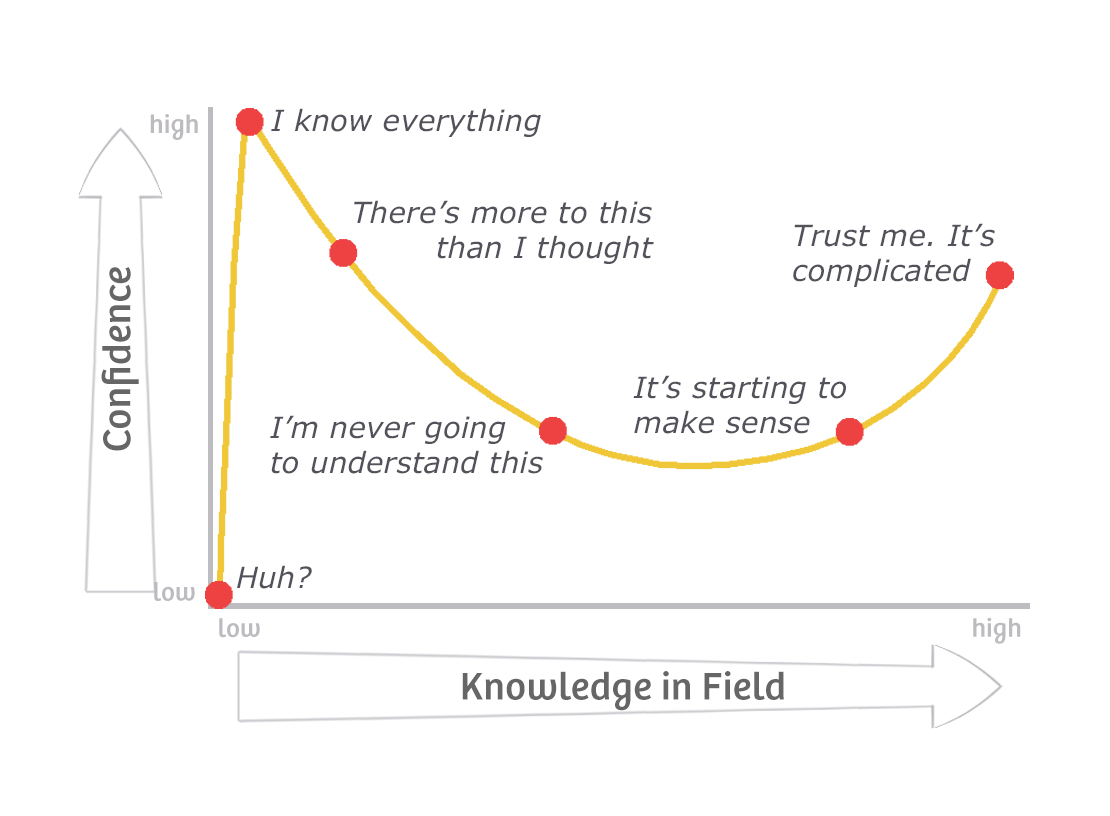

As you begin to learn a skill, it’s easy to start feeling incredibly confident. Speaking from experience, it can be tempting to follow the path of least resistance with your learning, just sticking to projects that reinforce your existing knowledge, rather than truly challenging yourself by diving deep or branching out. This overinflated confidence has a name, the Dunning-Kruger effect, and it can lead to nasty surprises if you’ve talked up your knowledge in a topic and then can’t actually deliver on it when others are relying on you. Understanding the Dunning-Kruger effect will help avoid this and make you a more mature learner.

How do we actually become knowledgeable and avoid falling into the overconfidence trap? A mentality that works for me is to embrace the climb. I like to think of learning as climbing a mountain: it’s slow and involves hard work, and it’s easy to get discouraged looking up at how far there is to go. It’s tempting to think that once you get to the top of the mountain, you’ll have “made it” and can finally relax. But whenever I’ve reached one peak, I’ve always found that there’s just more to climb.

If you want to be truly knowledgeable, you just have to accept that there’s always more to learn… and keep learning! I try to learn every day, at least a little. By making learning a habit, I don’t have to rely on intermittent bursts of willpower.[5] Those sparks are too infrequent, and advanced topics require repeated exposure to truly sink in anyway. It’s also important to remember that there will always be someone who knows more about a topic than you… and that that’s ok. The existence of smarter people doesn’t devalue how much you do know.

Finally, data science is constantly evolving. Today’s most popular languages and frameworks are likely different than those in ten years. Python reigns supreme now, but Julia is gaining traction. Tensorflow didn’t exist six years ago but immediately dominated the machine learning space when it arrived. Continuous learning is essential to stay relevant. (Or, as with the COBOL Cowboys, wait a few decades and the market will come back to you!)

Focus on the finish line

As we’ve seen in this blog series, data science spans a wide range of fields, from statistics to analytics, software engineering and business intelligence. This range is so wide because the tasks of extracting insights from data and communicating those insights to others don’t fall neatly into one skill category $-$ the anomalies your model detects probably need to be saved in a database somewhere, and then they should populate a dashboard that’s intuitive for stakeholders, and then you should pull in more advanced statistics to increase model accuracy, and so on.

Unless you’re at a large company with the resources to partition out each of these steps to a different specialist, you’ll likely be expected to deliver on all of them. This can feel like a mountain of work outside your job description $-$ are you really supposed to just pick up Spark or Terraform, or stand up that database or create that dashboard when your recruiter only mentioned analyzing data in Python?

I think humility and flexibility are important as a data scientist, especially early in your career. Providing actual business value from machine learning involves far more steps than it may seem before you begin! Key decision-makers probably want an easy way to inspect results themselves, not a Jupyter notebook; a software company probably wants your model integrated into the product, not a random R script in S3. Focus on the deliverable: something that actually enables the consumer. Do whatever it takes to make this happen, whether that means picking up additional skills, talking to the end user in person, or redoing work to incorporate feedback.

By focusing on the finish line, you adopt a solution-based approach, not a tool-based one. The question becomes “what’s needed to get this job done?” rather than “what can I do with Python?” This is why I find the R vs. Python debates silly $-$ learn both, then use the tool that’s right for the job.

Concluding thoughts

When considering what skills to invest in, it’s easy to jump to the latest shiny deep learning package, rather than tried-and-true personal and interpersonal skills. Similarly, you can only get so far without building up some field-specific domain knowledge, the context that helps you identify the right questions to pursue. Perhaps it’s because these skills are harder to quantify, or they don’t fit neatly on a resume. But understanding how to best apply your technical skills to truly deliver business value is essential for being an effective data scientist. Invest time here and you’ll be surprised at how much more meaningful and enjoyable your work can become.

This series has covered a lot! We started by talking about how to navigate the diversity of data science roles before going into detail on statistics, analytics, and software engineering, and finally ending with business skills. To avoid writing a textbook for each post, I’ve focused on the essentials of each topic, the core skills that will let you hit the ground running in a new role. But of course, there are dozens of topics I didn’t cover: natural language processing, time series analysis, deep learning, cloud computing, and plenty more. This is where I leave you to identify the advanced topics you’ll need for a role you’re passionate about. You’ll do great. Happy learning!

Thanks for reading, and all the best.

Matt

Footnotes

1. Optimizing resource allocation

It may sound like this section is arguing that the work you want to do and what's best for the company are two separate and irreconcilable worlds, which isn’t necessarily the case. If you’re focused on delivering business value, i.e. doing work that truly drives positive change at your company, then these two worlds will neatly overlap. The issue is if you want to only build machine learning models and none of the steps around the models, such as cleaning data, building pipelines, and soliciting and incorporating feedback from users. Shifting your goal from doing “cool data science” to doing “impactful data science” will help your goals align with your company’s.

But you also shouldn’t expect your job to completely fulfill you professionally, and definitely not personally. When I wasn’t getting as much teaching as I wanted after leaving academia, a former boss introduced me to the Trilogy coding boot camp, where I now happily tutor. Indeed, this article by Kabir Sehgal in the Harvard Business Review argues that everyone should have at least two careers (!), as that lets you enjoy different jobs for what they do offer.

2. Empowering coworkers

An obligatory note of caution: it’s easy to introduce a ton of scope creep with one-off scripts as feedback from your coworkers comes in. As best you can, try to establish the scope upfront, defining the point after which feedback is be treated as a feature request with a slower turnaround time. Similarly, to avoid taking on too much tech debt, at some point it will be important to modularize the code to make it easier and safer to modify.

3. Understanding the market

These two forms of innovation come from this interesting article by Pan Wu, a manager of data science at LinkedIn.

4. Understanding the market

When I was an undergrad, a mentor of mine said that she had pursued a Ph.D. to learn how to ask better questions. I found this focus on understanding what to ask, rather than how to answer any question, incredibly insightful.

5. CI: Continuous Improvement

Habits researcher James Clear argues that the most productive people are those who struggle with self-control the least. It’s a counterintuitive idea that changed my perspective. The key, he says, is to structure your environment such that you minimize the amount of self-control you have to exert. If you’re trying to lose weight, bury the cookies in the back of a high shelf. If you want to read more, place a book on your pillow so you’re reminded when you go to bed. Clear’s book Atomic Habits is full of useful tips like these.